Philippe Auclair (Louis Philippe) reflects on the year

This truly has been the strangest of years for me, a year which started in uncertainty and ended with my adopted country’s final act of severance of its links with the European Union, something which has been a source of deep, in fact life-changing sorrow for me and so many of the people I call my friends here in London and elsewhere in England. I daren’t say more on the subject.

But then, sorrow and grief have been all-present throughout these twelve awful months. I said goodbye to far too many people who were dear to me. My beautiful friend Ken Brake finally succumbed to the cancer which had plagued him for several years, long before his time. I still find it very difficult to use the past time to talk about the musical accomplice of nearly three decades, the man with whom I shared more jokes and cups of Darjeeling tea than I did with anyone else during this time.

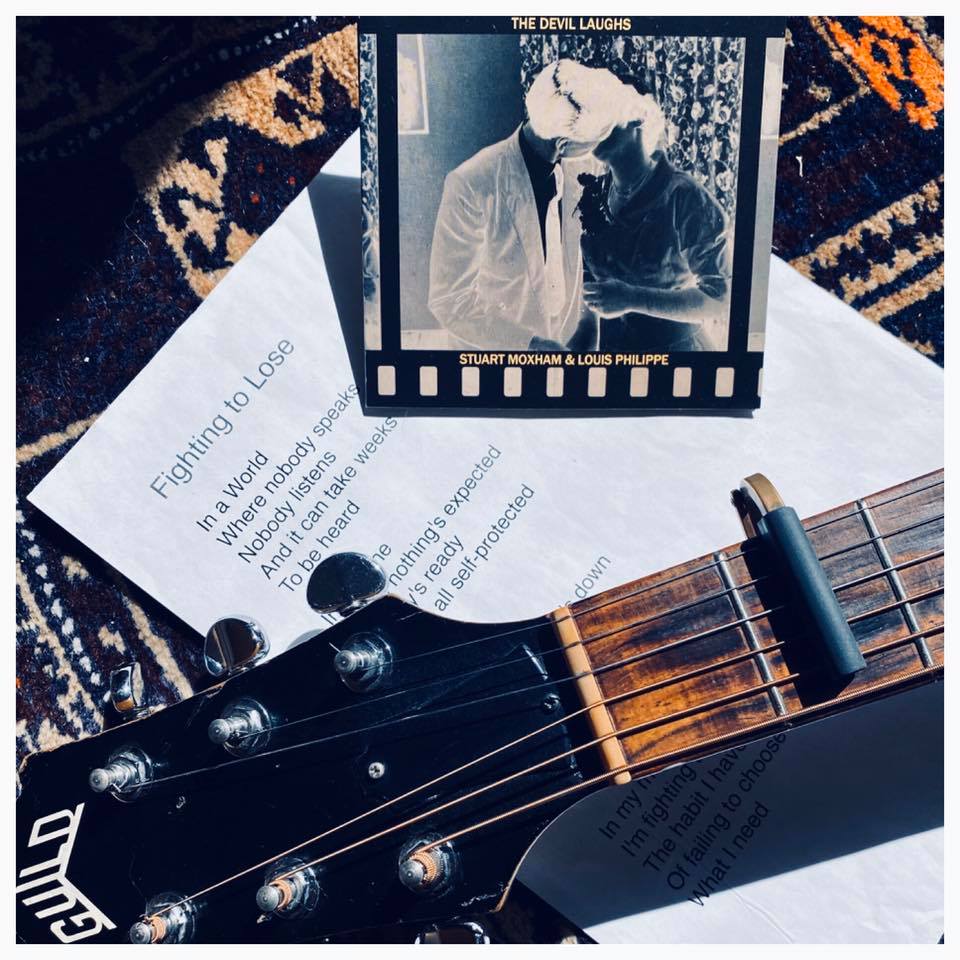

We made so much music together in his immaculate studio in Primrose Hill—just the two of us, or with Alasdair, Lupe and The Clientele, or Louise Le May, or Mari Persen, or Jonathan Coe, or, especially, our beloved friend Stuart Moxham. A small consolation is that Ken lived long enough to see the release of the album the three of us recorded over a period of years, The Devil Laughs, which, at times, I’d feared would never see the light of day—or not soon enough. Thank goodness—and thanks to John Henderson of tinyGLOBAL—The Devil Laughs was released in June, immediately earning the kind of critical acclaim that Ken so richly deserved to be associated with. Small mercies. Very small mercies.

So The Devil Laughs has to be on top of this list. Sadness tinged with hope and joy—that was 2020 to me, as to so many others. The joy came from music, first and foremost. Without it…

But there was joy too.

In music, to start with. It was a time of discovery and re-discovery.

The discovery of Igor Levit, for example, thanks to his astonishing interpretation—all eleven hours of it—of Erik Satie’s Vexations, which was streamed live on YouTube and was one of the most transcendent musical performances I’ve ever witnessed. A single page of music, which must be played 840 times in succession, was transformed into a genuine voyage of exploration, tender, angry, hypnotic, magical.

Christophe Chassol, a composer and instrumentist who inhabits a universe in which classical music, minimalism, retro-futurism and sunshine pop coexist in (beautiful) harmony, gave us his Message of Xmas (on Bertrand Burgalat’s label Tricatel), a musical UFO of the kind I wish visited our sorry planet more often.

I know absolutely nothing about another Frenchman, another Christophe too, called MOTTRON, whom I came across thanks to the recommendation of Chris Evans, the presenter of “The Curve Ball,” a show which plays the kind of music you won’t hear anywhere else, but which, in a better world, should be our lives’ sonic landscape. It is totally original. It also completely disappeared under the radar, and I get the feeling Mottron himself doesn’t mind it that much. Give it a chance. It’s on Bandcamp. “Indecent,” the third track on his debut album, Giants, is breathtaking.

I had no idea that Petter Herbertsson of Testbild! had another parallel project, Sternpost, or that he’d released Statues Asleep on the Kalligramofon label. This is Petter at his most cinematic and melodic best, with vocal textures which are unmistakably his and his alone. He has a way with harmony which is also entirely personal—now how many musicians can you say that of?

The song I listened to more often than any other in 2020 was Lô Borges’s composition “O Trem Azul,” as sung by Milton Nascimento on their Clube de Esquina double album, a record that will soon be fifty years old, and is yet unsurpassed. It is the song that the Pale Fountains, Everything But the Girl, Aztec Camera, Prefab Sprout, every Sarah band (and myself) have been trying to “find” throughout, the absolute matrix of perfect pop. Paddy did. It’s only taken me something like twenty years to realise this.

I’ve still got four spots to fill. I’ll put the lid back on the record player, then, and go to the bookshelves, where four Japanese authors are waiting for me, all of whom I discovered in this shit year. All of them are women. One of the many wonderful things about late 20th-century and 21st-century Japanese literature (and manga) is that so much of it is— recognisibly—the work of women. I wish so much more in this fucked-up world were the work of women. There’s Natsuo Kiriko, whose brutal Out shook me to the core (Grotesque and The Goddess Chronicle popped in the post this morning). Sayaka Murata’s Earthlings is another genuine shocker. There’s Yoko Tawada’s dreamlike, strangely tender, dystopic novel The Lost Children of Tokyo. And, more than anything else, there is Yoko Ogawa, whose The Professor and the Housekeeper I would place alongside Tanizaki’s Makioka Sisters and Naguib Mahfouz’s Cairo Trilogy at the top of my literary pantheon. Its last chapter (and so much beforehand) moved me to tears.

This is the pain that does us good, as Léo Ferré put it. How we needed it in 2020.