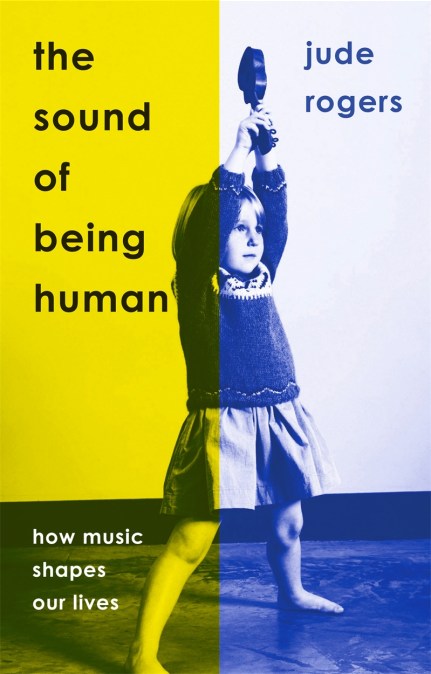

chickfactor is proud to present an excerpt from Jude Rogers’ excellent 2022 book The Sound of Being Human (White Rabbit Books/Hachette), which is now available in the US for you to purchase for all your loved ones immediately.

BUY HERE or HERE

Listen to Jude’s podcast here.

Read our interview with Jude here.

Track 5

Drive – R.E.M.

How Music Obsesses Us as Teenagers

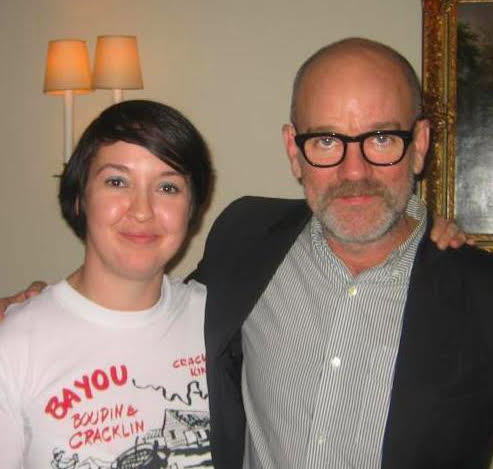

I walked through Mayfair in London on a cold, sunny November afternoon, along the sides of grand, leafy squares, towards a man with whom I’d had a relationship since I was fourteen.

When I first saw him properly, he was gliding over a sea of hands, wearing a shirt, white and crumpled, open at the neck. I saw the pale skin at his throat and the wide, flattened plane of his stomach. His shorts casually revealed his thighs and his calves. His pale eyes, his perfect mouth, his gawky jaw, looked like they were all carved out of marble.

I watched him being passed around like a god then tossed in the air like a plaything.

We spent days together in my bedroom after that, my door closed, my heart open, him whispering feverish things into my little pierced ears. He told me I was wild. He told me I was his possession. I listened, determined to live my life as he told me to live it, full of joy and wonder. Every night, I imagined reaching out and seeing him fully formed at the end of my bed, reaching out his hand, holding it in mine, the two of us sinking through the sheets, the earth, the whole universe.

My heart felt too full that day in Mayfair, rising up from my chest, like it was almost in my throat, or raw and ripe in my mouth. I had barely slept for nerves. We were about to have twenty minutes together, just the two of us, in a hotel room, for the first time.

*

There’s something intrinsically unhealthy about falling in love with a much older man when you’re in secondary school. At that age, you’re vulnerable, but you also feel invincible. Your every response, psychological, physical, sexual, is on high alert. You’re bloodily, feverishly, desperately alive.

Mr Seaton, a history teacher at my comprehensive, had made the introductions. At wet break-times, my friends and I would beg to be allowed in his first-floor room at the back of the tower block. We loved Mr Seaton because he had a poster of Evan Dando on his cupboard door and he would play tapes while he tried to get on with his marking. One day, he played Automatic for the People. I pestered him to make me a copy until he did.

Over the summer holidays that year, I found myself at a strip-lit urban cathedral in Leicester while on holiday at my new uncle’s house. The name of the megastore glared at me in big, knowing red letters. Inside Virgin, I went to R and found a small, jewelled box with a picture on the front of a thick, golden sea; I felt something inside me unravelling as I took it up to the till, my other hand gripping onto my pocket money tightly, anticipating what these coins could possibly provide in exchange.

I got back to my uncle’s front room, closed the door, unwrapped Out of Time from its cellophane, and ceremonially slotted it into the Walkman I’d been bought a few Christmases earlier. Peter Buck’s guitar strings sounded like spiritual sirens. Mike Mills’ brilliant basslines held the songs upright and straightened my spine. Bill Berry’s drums were unshowy and subtle, always in service of the song. Michael Stipe sang of fantasies flailing around, lonely deeps and hollows, barefoot, naked, on a maddening loop. His voice unfolded me like the concertina of cassette liner notes I held in my hands.

In my mid-teens, I pored over liner notes like ancient scrolls, and I especially loved the liner notes to Out of Time. The mysterious artwork on the front, covered by a yellow R.E.M. logo, was shown in full inside: I found out years later it was called Yellow Seascape With Film and Wood Blocks, made in 1988–9 by American artists and identical twins Mike & Doug Starn. The original suggests two doors that you can open, so you can take the handles in your fingers and comfortably enter the water. They made me want to open them, experience full immersion.

Inside the concertina, there was also a photograph by the brothers, of a plant, taken in black-and-white like a daguerreotype. There were others of fecund fruit and flowers and a cat’s orange tail, struck by sunlight. There were also two cartoons, one featuring a man in a hat, looking like Michael, staring into the window of something that was called a sex theatre. The caption said: ‘These faded, backlit transparencies remind passersby of the live spectacle happening inside.’ I didn’t want to understand what it meant, but also I did.

My fandom wasn’t just about the delivery or the storytelling, I realised quickly: it was about something bigger, a band as a complete work of art. Not long after, I saw the video to their 1992 single ‘Drive’, filmed in stark black-and-white, the scene occasionally blasted by spotlights and lasers. Michael Stipe was crowd-surfing through a huge, pulsing audience, their hands raised to hold him, their fingers at full stretch, heated and hungry, their faces rapt. Sometimes, Michael looked numb, paralysed at the mercy of the mob. At others he looked ecstatic, his arms stretched out as if for a crucifix, blissfully accepting his fate.

It didn’t sink in with me initially that the lyrics to ‘Drive’ were inspired by the idea of young people being politically mobilised. It was a song directed at American youth: youth that felt whacked out by a presidential term of George Bush after two terms of Reagan; youth that were fed up with being told what to do and where to go. ‘Drive’ was even used in a campaign to make voter registration easier in America, a ‘drive’ that later succeeded under Bill Clinton. I was more interested in the emotions in Michael’s delivery than distant political machinations, in the way that he sang ‘hey kids’ like a mysterious invitation, like a breathy Pied Piper.

*

Years later, I’d find out that ‘Drive’ harked back to Michael Stipe’s youth. ‘Hey kids’ was a line lifted directly from one of his favourite songs as a teenager, David Essex’s peculiar, perfect dub-like 1973 debut, ‘Rock On’. Michael talked about the effects of its weirdness on him in 2017, in an interview with NPR in the US, marking the twenty-fifth anniversary of Automatic for the People. ‘[It] just blasted right into the core of my being as a thirteen- and fourteen-year-old, I think, and presented to me this kind of set-up for what Patti Smith, CBGBs, Television, the punk rock scene in New York in 1974 and ’75 would offer me. It was an entry into a universe that accepted me for who I was. I was already at that point where I realised that I was very different from all the kids around me . . . not eccentric, I never like that word.

But I was different.’ ‘Rock On’ provided him with a key to a new door. ‘A door that would open and never shut again.’

I used to watch ‘Drive’ on my own, on our video player, when I was meant to be doing my homework while my family were out. I had a baby brother now, James, a sweet, chatty toddler. Jon had just reached double figures and was getting into music too. Every Saturday, we’d sit and watch The Chart Show on ITV, taping songs that we liked, taping over others that hadn’t held our interest after a few weeks. Given our different ages, the results were usually a hysterical mish-mash of sounds and styles, my nascent interest in indie buffering around videos by Lionel Richie, KWS, Mr Blobby.

I didn’t want R.E.M. to be for my brothers’ eyes, though. R.E.M. were exclusively for me. I’d wait until my parents would go out with the boys, hearing the car reversing up the drive on the way to the supermarket, to my grandma’s, to Cubs, and I’d let the reels roll and sit motionless in front of the screen. Often, I would watch ‘Drive’ on repeat. It was a strange thing for me to keep watching, because I didn’t like crowds. I found them claustrophobic, frightening – but this was one into which I could safely fold myself, imagine as a launchpad to future experiences, to test out the thrill.

The arrangement of the song built in intensity slowly, giving it a mood which was also slyly erotic. Halfway through the video, the crowd are blasted by a fire hose. The other band members stand in front of them, grinning, their instruments soaking wet. It’s a knowing release.

The words Michael sang also added an element of flirtation into the mix. There is innuendo in the line ‘What if you try to get off?’ which I’m sure I didn’t get at fourteen. I know I felt the word that followed it, though, an old trick out of rock and roll’s playbook, one I already knew from songs by groups I’d loved a few years earlier, like Bros and New Kids On The Block. This time, the word carried a different weight in Michael’s mouth.

‘Baby,’ he called me.

*

My love of Michael Stipe came in that peculiar period between worshipping saccharine boy bands and my GCSEs, when the teenage brain and body feel like they’re aflame. Neuroscientist Catherine Loveday mentioned this stage of development when we spoke about our fathers. We often return to the music of our teenage years in tough times, she’d said, because this is when brains and bodies are developing at their quickest rate.

I Zoom her again, and she tells me this rapid development in adolescence is a relatively recent discovery in neuroscience. Twenty years ago, it was thought our brains stopped developing in mid-childhood. Now we know there are huge surges of development that come later, particularly in a network of structures colloquially known as the social brain. This includes the anterior cingulate cortex, a region important for understanding and empathising with people, and the fusiform face area, which helps us recognise faces and process the emotions they are exhibiting. As teenagers, we are drawn more to new faces and wanting to understand them, Loveday explains, even if they are just faces on a screen.

Parts of the brain’s subcortical structure are also developing and maturing. The amygdala attributes meaning to the emotions we are feeling, while the nucleus accumbens acts as the brain’s interface between our motivations and actions. Both have to communicate with the faraway prefrontal cortex, at the front of our brain, which is responsible for how we control our behaviour. ‘These subcortical parts are about generating emotion, really a kind of unconstrained emotion, if you like – while the prefrontal cortex helps us to regulate what those emotion centres are doing.’ Then Loveday introduces a theory in neuroscience called the mismatch hypothesis, which suggests that the prefrontal cortex can’t keep up with the pace of the subcortical surges.

Loveday refers to the work of Sarah-Jayne Blackmore, a neuroscientist who wrote Inventing Ourselves, a book looking at different systems of the teenage brain. Blackmore’s analogy is that the experience of having a teenage brain is like having a very fast car with lots of power, but no steering wheel: sensations of exhilaration and elation are everywhere, but without the tools to handle them properly, to rein oneself in.

The dopamine pathway that connects these subcortical areas to the prefrontal cortex is also developing quickly, speeding up the passage of feelings of pleasure. ‘This pathway is really important for feelings of reward and obsessions,’ Loveday says, ‘obsessive love, and that kind of thing, which gives you an appetite, an active drive, to seek novelty.’ The increased activation in this pathway is especially important in evolutionary terms: as they move towards adulthood, young people need to move away from their families to seek potential mates, and not have incestuous relationships. Another thing can also activate this pathway, Loveday says: ‘It has also been shown to be activated by music.’

I think of myself in my bedroom, kicked into life by the rushing sounds of bright guitars, Michael Stipe’s voice in my little speedy-head, telling me I’ve got to leave to find my way. The sensations back then were romantic and thrilling; I really felt like I loved him, that I wanted him to consume me completely.

Loveday then mentions another neuroscientist, Kim Lyall, who went into an fMRI scanner in 2011 to make herself orgasm, to see which parts of the brain were aroused. ‘It’s a study my students are always embarrassed by when I talk about it,’ she says, with a smile. ‘But when people have gone in MRI scanners to listen to their favourite songs, precisely the same areas are highly activated as Lyall’s.’ That dopamine pathway can also become triggered by people, so if you are experiencing that feeling in your brain while somebody is singing, then effectively they become associated with this kind of brain orgasm. There’s also oxytocin being released, which gives a person a feeling of attachment and connection – but it can also shut someone off from other people who aren’t in their blissful bubble. ‘So what’s going on in your mind is, wow, this piece of music is amazing, isn’t that person fantastic – the brain is reacting as if you were actually close to that person and possibly even having sex with them.’ She laughs. ‘And yes – it can be quite overwhelming for people.’

I watch ‘Drive’ again at forty-three. I see other details. I see Peter Buck smiling as he’s soaked, a fan’s hand on his shoulder. On a few occasions, Michael looks at a fan and their eyes lock for a moment. Once he looks straight at the camera and sings at us. At me. I think about how fans and artists feed each other and seduce each other.

I look up Peter Care online, a filmmaker born in Cornwall who has long lived in LA, who directed the video to ‘Drive’. His early work was experimental, with Cabaret Voltaire, Clock DVA and Killing Joke, before he bagged bigger jobs with Belinda Carlisle, Roy Orbison and Tina Turner. In 1991, he was working mainly in commercials, and had had enough; he called his friend Randy Skinner at Warner Brothers to see if she could give him something more meaningful. He tells me what happened next on the phone on a hot Californian afternoon, as I sink into the sofa on a warm British spring evening. ‘I just couldn’t do it any more – I said, I’ll work for free if needs be, for any little tiny band with no money. And she said, well, have you heard of R.E.M.? And I was like, what?’

Peter knew them well. He had loved their early videos, and they’d just released a slicker proposition on screen that went on to win six MTV Video Awards. The video to ‘Losing My Religion’ helped propel them into the mainstream and did so without surrendering the band’s commitment to weirdness. It referenced Caravaggio paintings, the art of Pierre et Gilles and a pivotal scene in Andrei Tarkovsky’s film The Sacrifice, in which people in a room run from left to right past the camera and a milk jug shatters to the floor.

Peter signed up.

His first job with R.E.M. was ‘Radio Song’, and his video played around with ideas of the band’s changing identity. The four members held up moving images of themselves, and were surrounded by others on TV screens; vintage film was mixed in that recalled their earlier, scratchier style.

Michael then invited Peter to lunch and asked if he’d be interested in making ‘the greatest crowd-surfing video of all time’. He wanted to go shirtless, he added, and leant across the table, opening his buttons to show he’d already shaved his chest. ‘He also wanted it to be out of sync,’ Peter says, ‘to look really off. “Peter – everything’s off!”’

But the director was unsure about the idea of the frontman going bare-chested. ‘And I’m surprised he didn’t tell me to go fuck myself, but I said, it’s going to look a bit like we’re doing an Iggy Pop, and I don’t think that’s right.’ He suggested Michael wear a white shirt instead, so the audience could see it getting wet. ‘I said with a white shirt, there’d be a romance to it, a bit like the white sheets in The Death of Marat.’ I look up this picture after our call: it’s a famous painting by Jacques-Louis David of the murder of a French Revolutionary leader. There was another painting Peter had in his head too, by French Romantic painter Théodore Géricault, called The Raft of the Medusa. ‘I said to Michael, it has a crowd with their hands up, a storm, water, and it’s painted to look like the night with the stormy clouds, but it has a humanity to it.’ The references were a bit over the top, he says, self-deprecatingly, ‘but drama is something we gravitate towards when we’re young, and Michael was up for it. And Michael was like, “OK! All right!”’

Peter’s crew shot for two nights at the Sepulveda Dam, a three-mile-long feat of engineering near Los Angeles, constructed after the great floods of 1938, which killed over a hundred people. A radio call for R.E.M. fans saw hundreds turn up each night. A low-budget Lenny Arm crane was used to hold a camera and film everyone from above; it was wound loosely, creating a juddering effect, intensifying the strangeness with which Michael’s hero-worship was being presented.

Peter did five more videos for R.E.M. after that, in which he explored the attention Michael received in more detail. In ‘Man on the Moon’, Michael looks like a movie star in a cowboy hat, doing Elvis impressions, jumping on trucks, confident and charismatic. In ‘What’s the Frequency, Kenneth?’, he’s suddenly reluctant: shot from the chin down, in rock star T-shirt and jeans. In ‘Electrolite’, he’s filmed upside-down with plastic toy reindeer, in roller-skates, then pretending to be interviewed, then singing, hamming up his lip-syncing.

Peter emails me a few weeks after our phone conversation to offer more thoughts on capturing the feelings of the crowd in the ‘Drive’ video. ‘I wanted the camera to focus on Michael like a fan would – all love, fascination, and no irony . . . I never thought the crowd were expressing adulation exactly. The people there were all big fans of R.E.M. of course, and Michael held them in the palm of his hand during the whole shoot. But like any mosh-pit, there was an energy beyond fandom, beyond what would normally be focused on the star on stage.’

To Peter in 1992, a mosh-pit ripe for crowd-surfing was more about the camaraderie within it, the shared experience it offered, and the job it had to do: ‘i.e., don’t drop the crowd-surfer,’ he says. But then in 2001 he went to a pop video convention and saw ‘Drive’ on an enormous cinema screen for the first time. ‘That was a revelation for me – magnified hugely, I saw faces in much more detail, their smiles, their anticipation in waiting for Michael to come their way . . . [they were] so much more powerful as a group of individuals.’

I used to imagine myself among them, my hands lifted up, as I sat on the living room carpet. From the vantage point of adulthood, I remember how isolating it felt back then being in my early teens. In the pre-internet age, I could only imagine being around people like those in the dam, all looking for a way to look up and grow up.

This excerpt has been published with the permission of the author. Buy your copy of the book here or here.