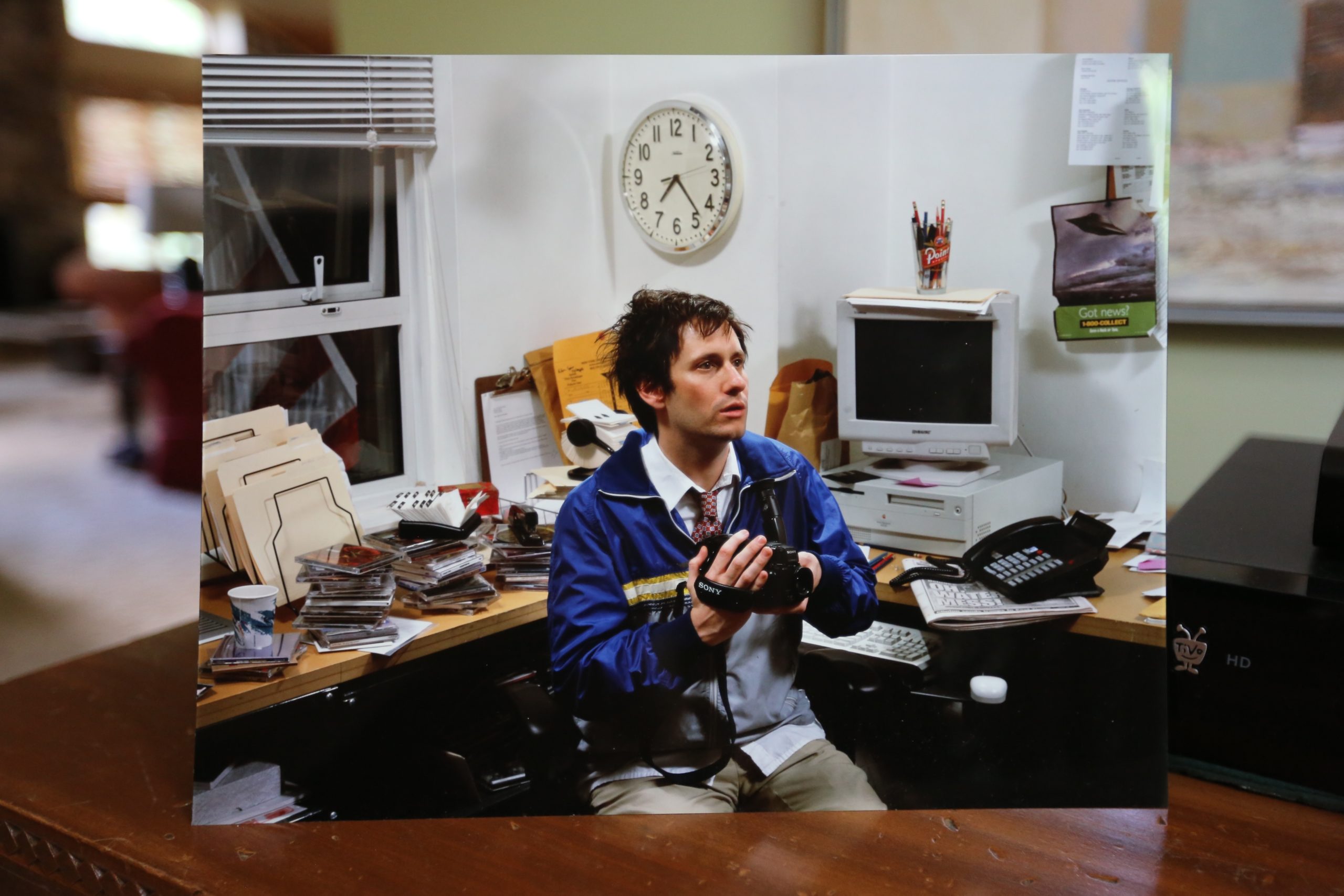

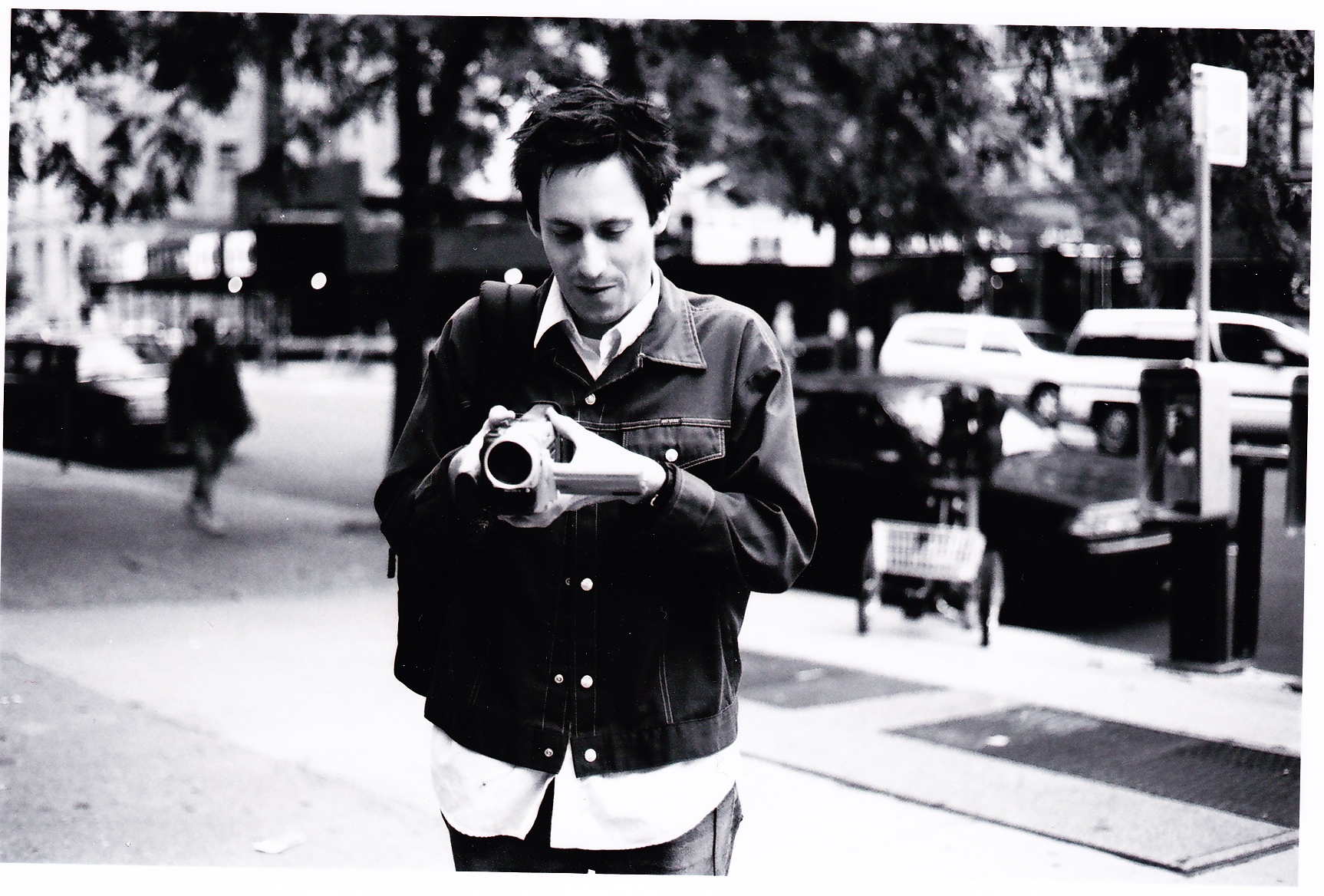

Record stores, collecting records, WFMU, selling out, underground culture from the 1980s and ’90s, the value of a creative life, indie cred, and unfinished projects—these are things we understand, don’t we, dear reader. I first met Chris Wilcha when I was an editor at SPIN magazine and he was an intern, and he interviewed me about chickfactor as if he were already a documentary filmmaker. After getting a job in the “alternative rock” copywriting team at the Columbia House Record & Tape Club (where you could get, like, 10 vinyl LPs for a penny) in the grunge era, Chris brought his camcorder to work and documented his experience struggling with working for The Man; the result was his first documentary, the acclaimed The Target Shoots First (2000). After piloting a TV show for This American Life (2007), he became a family man and commercial director, though he remained a doc maker in his brain. He also worked on projects with Judd Apatow, Coen brothers and Tig Notaro. His new film, Flipside (2023), chronicles not just his formative years working in a Jersey record store, but how music and possessions influence our identities, moving on and letting go, and how it’s a shame most of us are doing creative work as a labor of love (and are often exhausted by our paid work). We caught up recently and had a chat and here it is. Images courtesy of Chris Wilcha and Tracy Wilson

Flipside will be in theaters in NY starting May 31 and Los Angeles starting June 7 and streaming soon thereafter

chickfactor: When did you intern at SPIN (you were known as SPINterns)? What was your impression of the magazine? The other interns? What exactly did you do while there?

Chris Wilcha: I was a SPIN-tern in late 1992, early 1993. I have this distinct memory of walking back to my apartment on 13th street after an afternoon working at SPIN and the first World Trade Center bombing had happened earlier in the day. So yeah, that was February 1993. I had been such a loyal and avid reader of the magazine before interning there. At first it was kind of thrilling to meet all of these people whose bylines I’d been reading but then it all gets demystified pretty quickly. You kind of realize that they are all varying degrees of miserable or at least annoyed by your presence. It was so useful to see the day-to-day grind of working at a magazine, to see how it gets put together every month. You were very nice to me. And you seemed incredibly meticulous and skillful at your job.

What did you learn from working at SPIN? Anything valuable?

It was a pretty classic internship experience, a lot of menial tasks. I remember getting Bob Guccione Jr. shots of espresso before meetings. There was one great perk. I was allowed to pitch ideas and write something for the magazine. And a couple of things I wrote ended up in the magazine. One was a short piece about frizzy haired public television painter Bob Ross. A reappraisal of his brilliance. He was still alive then. I was very early on the Bob Ross pop culture appreciation trend. But I definitely used that clip to get other writing work. Years later, in 1999, SPIN did a piece on my first documentary, The Target Shoots First, and that was truly thrilling.

Let’s talk about your early days in New Jersey. How did you find out about music? What was your first concert?

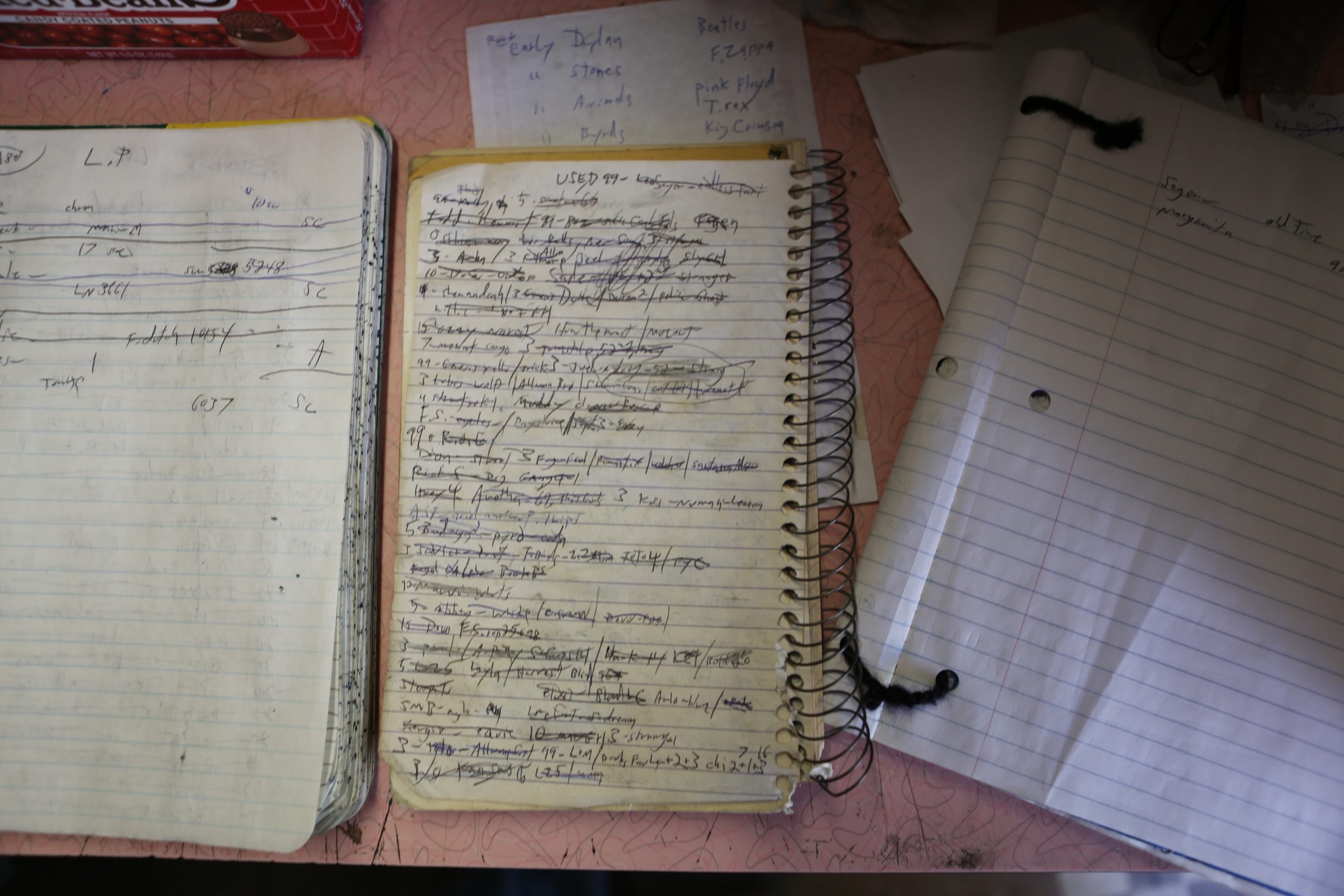

I was playing in classic rock bands in high school and learning guitar. The first concert: My dad took me and my friends to see Van Halen at Madison Square Garden in 1984 for my 13th birthday. I was definitely guitar shred culture obsessed. My mom wanted me to read, so she got me magazine subscriptions to Guitar Player and Musician, Circus, SPIN, Creem, Rolling Stone. I still have them all. Musician had a column where artists would explain their gear in great detail. The Replacements were having a mainstream moment and they did the gear sidebar, but they totally mocked it. They were like, “Tommy plays a red guitar, Paul plays the blue guitar.” It was like a fuck-you to the whole gear-obsessive nerd thing. This was all pre-internet so I was obsessed with information and knowing things about music and bands gave you a certain currency.

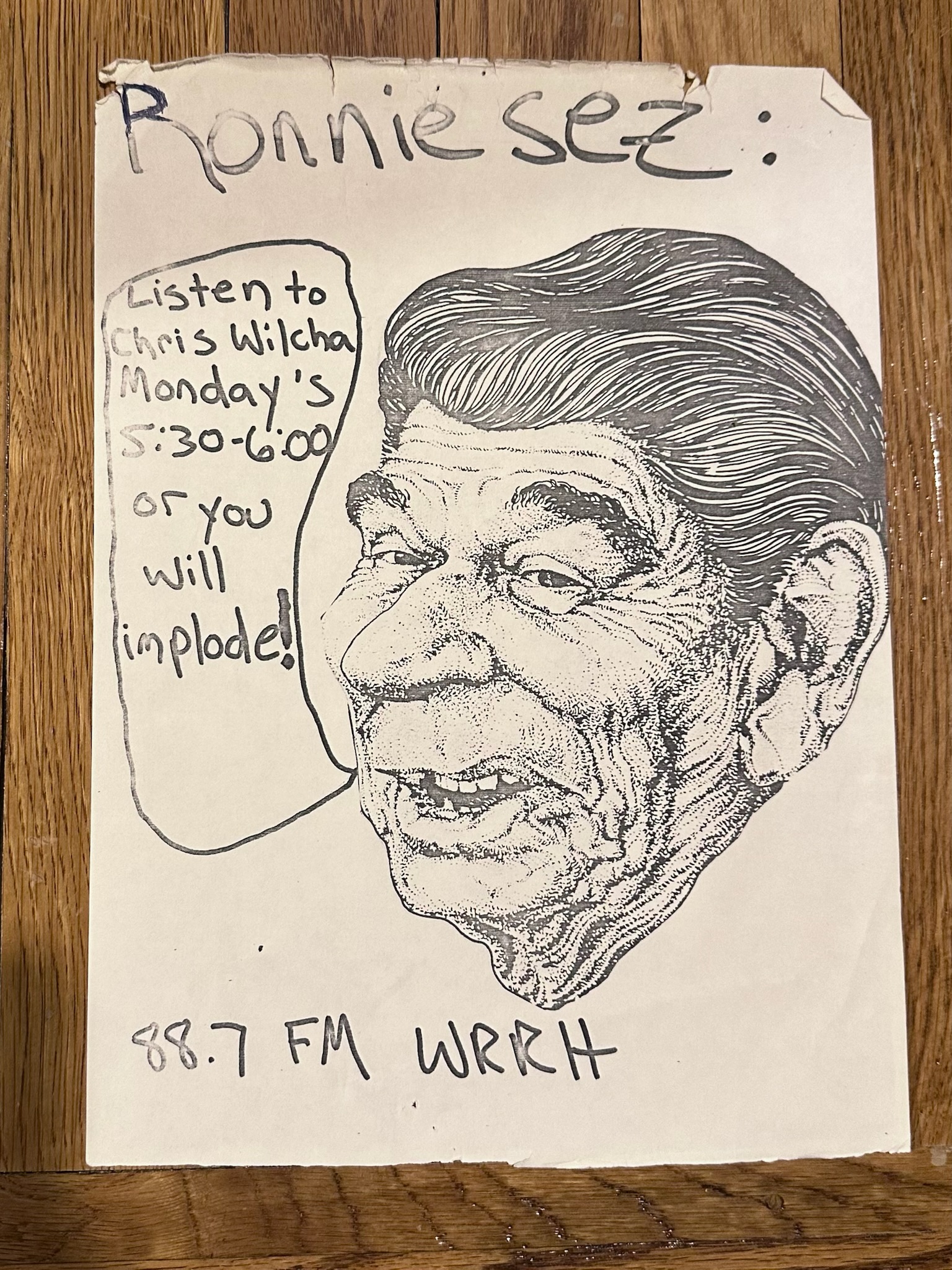

My older sister had some boyfriends who were in the know, they were going into the city, seeing shows, and they clued me in to college radio stations like WFMU and WRPR. And that was when I started listening to hardcore bands, college rock and what eventually became known as alternative music. That was the golden age of college radio. I remember being totally mystified by what I was hearing. One time the Butthole Surfers song “Moving to Florida” came on and I just had no context for what the fuck I was hearing. These albums seemed so transgressive and fucked up and my very young 13-14-year-old brain was trying to process what this stuff was. I was getting it as this big stew though, so it was hard sometimes to know what was corny and what was interesting.

What was your sister listening to?

She was very college rock. R.E.M. and Talking Heads. Tracy Chapman. She took me to see a midnight screening of Stop Making Sense in the city. A friend’s older brother took us to see Bad Brains and that was genuinely kind of astounding.

That sounds like 1985-86-ish?

Absolutely. I was recording things off the radio and sometimes I didn’t even know what I was listening to for years.

When you were listening to something back then, it felt like, “I may never hear this again and I’m going to be so sad about it. I may never even know who it is.” So where did you hang out? Did you grow up in the Flipside town?

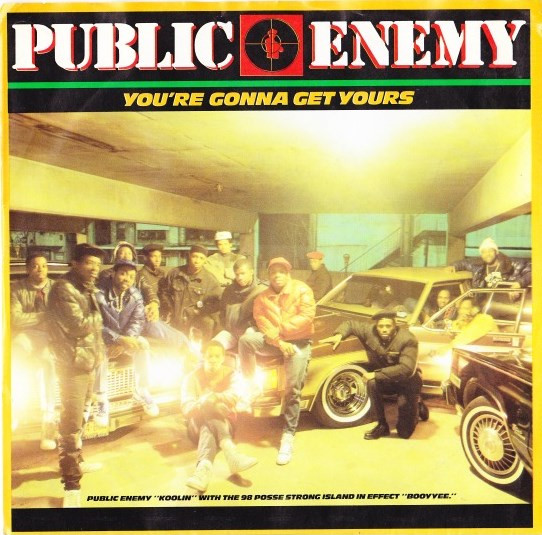

I grew up one town over in Franklin Lakes and the record store was in Pompton Lakes. I couldn’t drive, so my parents or my sister would have to drive me. Eventually I drove, and I remember listening to records always back and forth. My dad had a company car, a perk of corporate culture, a 98 Oldsmobile. This was the mid ’80s. I would drive his 98 Oldsmobile to my job at the record store. There was a Public Enemy song on their first album called “You’re Gonna Get Yours,” which was about how they were fetishizing 98 Oldsmobiles. I remember playing that song in my dad’s car as I was driving his 98 Oldsmobile. That just seemed so funny to me at the time.

I would sneak into the city a lot. I wasn’t totally embedded in the social universe of my high school, but when I got into a band, I had this double life where we would go play in other towns and Battle of the Bands or parties. I was meeting all these people in this weird northern New Jersey circuit of schools that never would have had any exposure to. Playing in bands felt like this weird passport to all these other experiences. We were just a terrible cover band, but it was super-fun.

Back then you could go anywhere as a kid in NYC, nobody cared, pre-Giuliani.

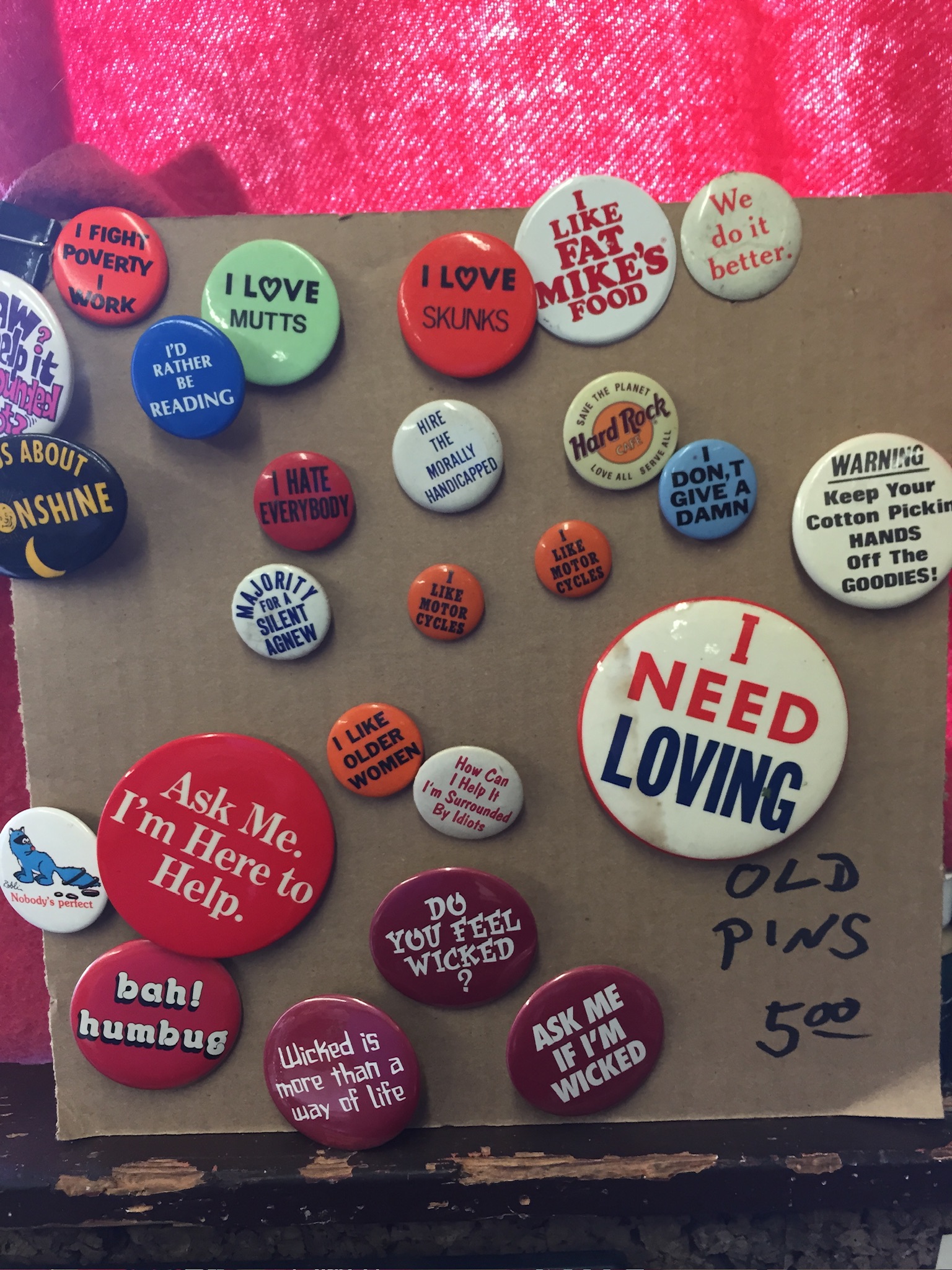

Anywhere. CBs, CBs Gallery. We did some really dumb shit. I had some metalhead friends and one night we went to see Celtic Frost [laughs] and everyone drank too much and the kid who was the designated driver was totally wasted. So somebody else drove us home who was like probably 15, super-dodgy—dumb high school, no frontal lobe decision-making type of stuff. I truly was obsessed with music. If I wasn’t playing in bands, we’d go into the city, to Tower. Bootlegs were this mysterious oddity that you could get on St Marks. Hip-hop was this new nascent thing. I was obsessively consuming stuff about music. That’s why the record store job that eventually happened in high school was the dream. I had done shitty jobs before that: caddy at a golf course, mowed lawns, all the classic suburban shit. But the record store job was the first time where I was like, Oh, I don’t even notice the time passing. This is just pure pleasure. It was also like a social hub. You would go there to talk about records and new releases and people would just hang out for hours at the record store.

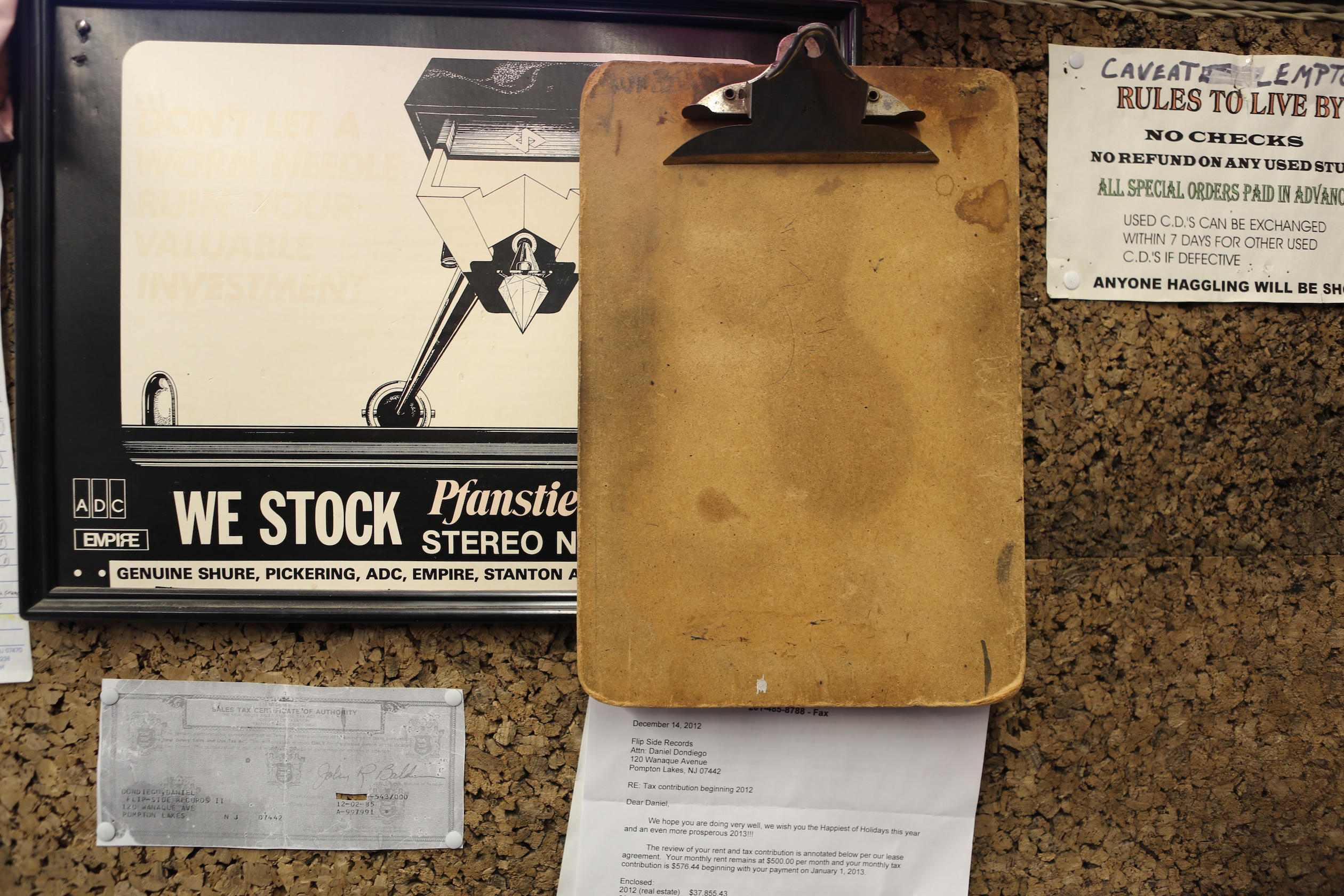

Is Flipside Records still open? What was it like then versus now?

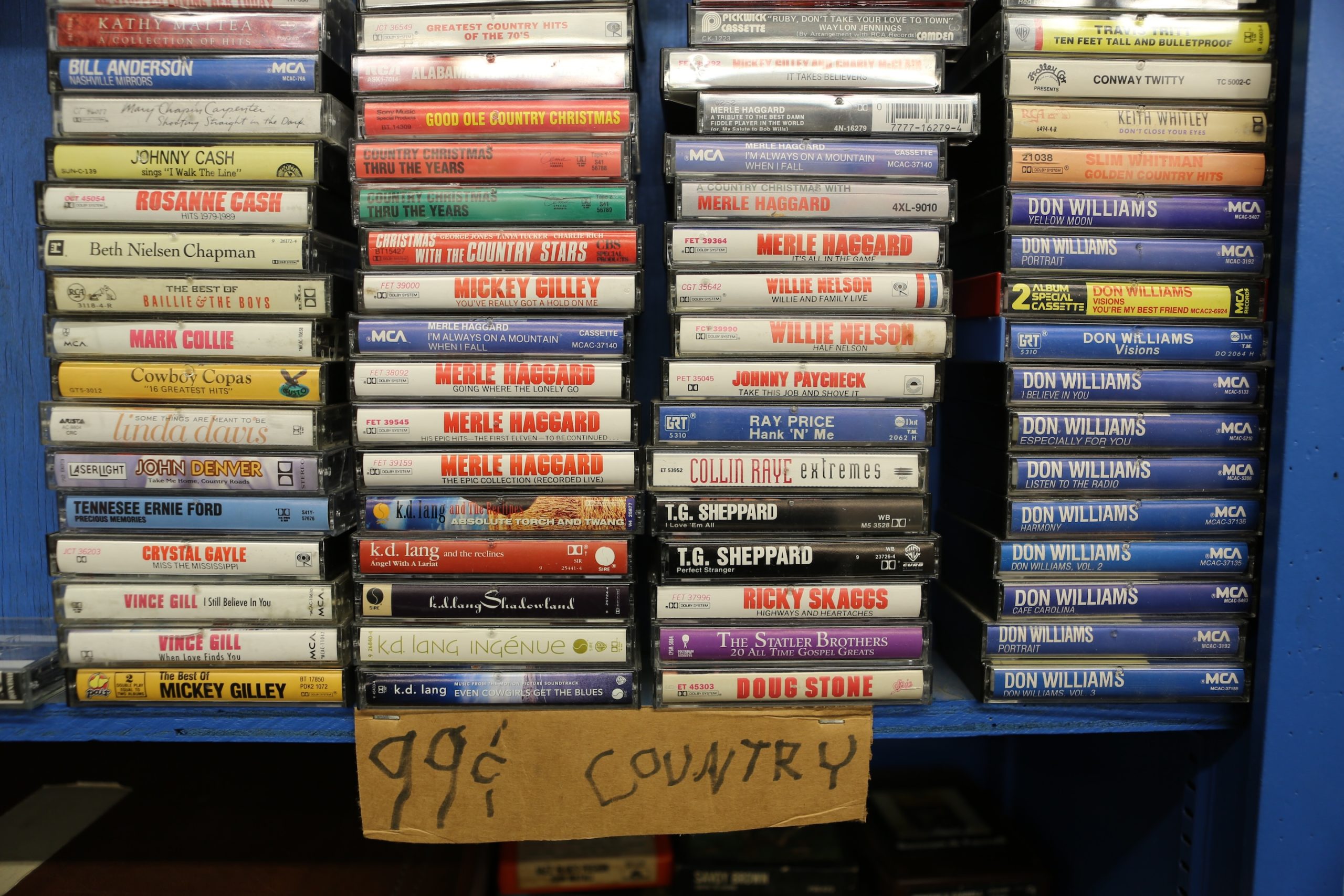

It is. Back then it was new releases of every kind. A person would come in and they’d want something that was on the radio that day in cassette form. Or a kid would come in and he’d want some metal thing he’d read about. The inventory was totally new, it was constantly turning over. They also had cutouts—I’ve since read that there was a sketchy market for them that had some kind of mob-related thing where sometimes and there’d be a saw mark in the cover of the vinyl, there would be a gouge in it. The owner, Dan, always had some line on cutouts where it was like $3.99 for these things. He also had bootlegs and he sold VHS. He would run dubs of like weird art movies or horror movies. A mom would come in looking for a Tiffany cassette.

There were these odd little footnotey New Jersey microcelebrities who would come to the store. The Feelies were a big specter to me, like wow, the Feelies, and one of Dan’s close friends is Dave Weckerman, who’s in the Feelies. I remember seeing the movie Something Wild and there’s the Feelies and Dave is playing in the band in the Jonathan Demme movie and then he would come into the record store. He was like a celebrity to me. Various other characters: This guy named Bobby Steele was a grungy New Jersey hardcore guy who played in The Undead who would come by and drop off stickers and zines and cassettes; Uncle Floyd, this cable access character in the tristate area, would shop there because he’s a record-collecting obsessive who had various radio shows.

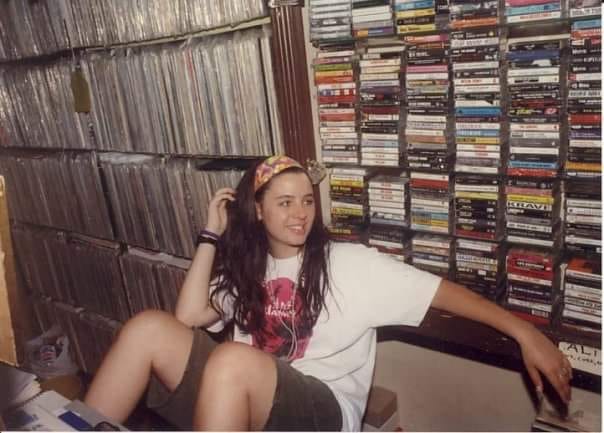

There was a whole universe in the store and the town that was just very formative and made a big impression. There was also this micro regional celebrity that would come along with it, which is you were known as the person who worked at the register, and Tracy (Wilson), who succeeded me, ended up really embracing that role. Dan saw that she knew her stuff and he let her and some of her coworkers buy for the store. Her taste was so sophisticated, and she knew bands and a whole market that Dan didn’t understand at that point, and he saw the wisdom in handing it off to Tracy.

Tell us a funny story about something that happened there.

A friend of Dan’s would come into the store, Rick Sullivan. He was a bit of a New Jersey character who did a zine called the Gore Gazette and his obsession was horror and B movies. His expertise and knowledge were fairly astonishing. These guys drank like fucking fish. They’d come in sometimes on Fridays and hang out and start drinking at around 3:00 p.m. and let me drink with them. One time I was in the store completely alone. This woman comes in and starts asking me about a record, and then she gets weird on me and a little flirty and I’m confused because this is an older woman and I’m 15, 16 years old. Eventually she overtly propositions me and my jaw’s on the floor … I don’t even have the language because we left the realm of the normal. This is like Weird Science. And of course, Rick comes in a minute later and he’s like “AH HA HA.” He had put this woman up to completely fuck with my mind. I was so paralyzed with high school awkwardness and utter embarrassment.

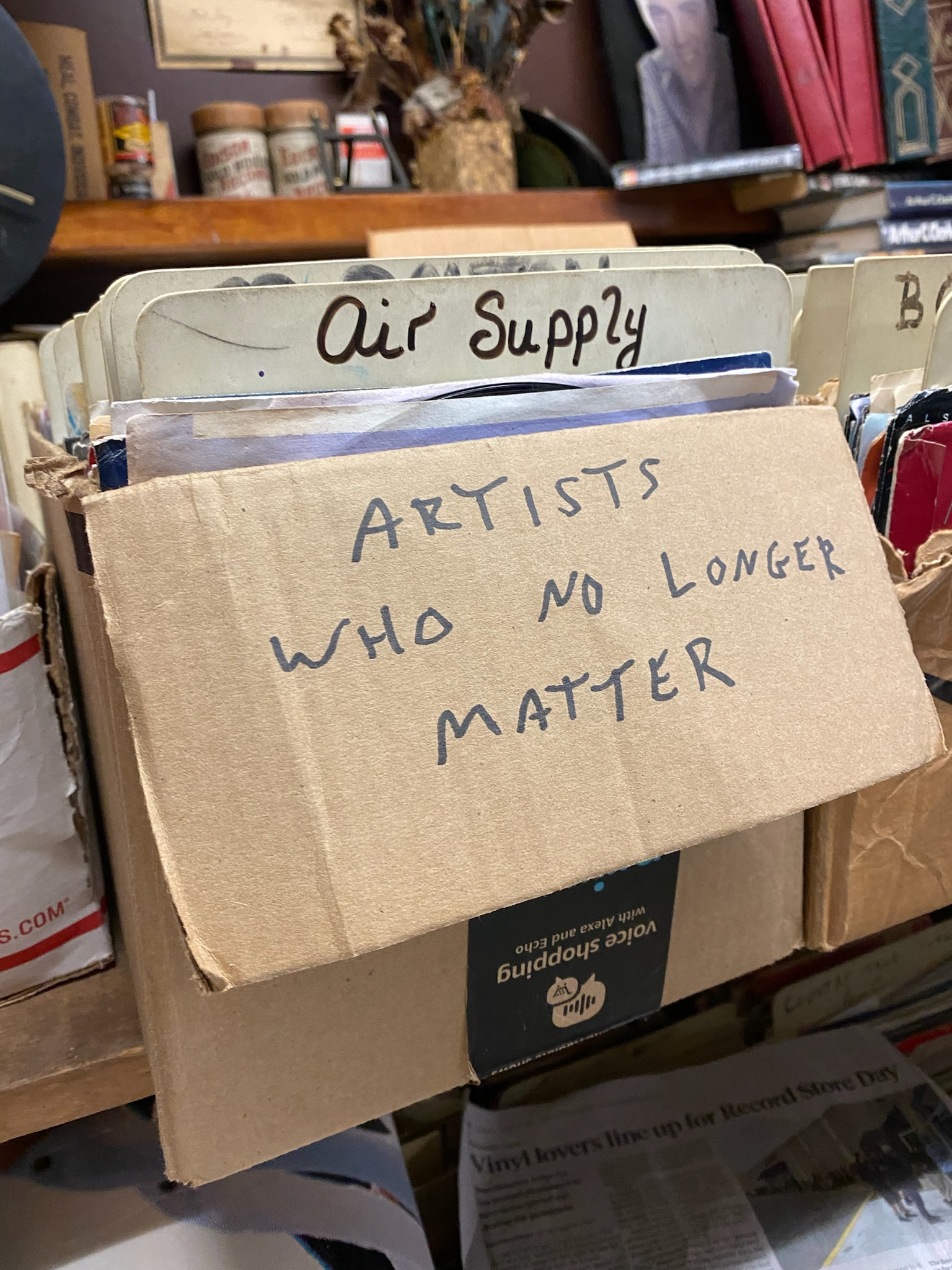

The film explores how our possessions and musical taste affect our identity and the idea of hoarding versus collecting.

The entire experience of making the documentary helped me figure out what I wanted to keep and what I wanted to leave behind at this midlife moment. That meant both going into the closet and interrogating these things and saying, “does this retain some meaning”? I would often acquire things thinking, I’ll make something of this at some later date. I’d go to a garage sale and say, I need this person’s entire collection of slides because I am going to make something out of it, a short film, sort of object or sculpture. There was this weird hoarding mentality.

And it could be the next Vivian Maier, you never know!

Totally. I was also thinking about ideas that you’ve carried with you for a long time that it’s time to let go of. There was also the Gen X obsession of the ’90s was this whole idea of selling out and that was something I thought about, these nuances of who was or wasn’t selling out.

We couldn’t escape conversations about selling out in the ’90s. Nowadays no one would accuse you of that because musicians can barely afford to live.

It’s so brutal. I saw Dan Zanes play and we were remembering when the Del Fuegos did a beer commercial and there was backlash that hindered their rise, which seems insane now. But I mean, I love stuff. I loved garage sale-ing and thrifting and acquiring and saving. There was always some renewed awe when I would rediscover the things. I also moved a lot, but I had this home base of my parents’ house [for my stuff]. They never did anything rash like throw it out; they knew it was significant and important. And as you see in the movie, my dad also has some of these same acquiring, keeping tendencies.

I never got any pleasure out of selling stuff. It was always the acquiring … it was like going to the museum. It was this other form of culture consuming. But then I had a family and we moved into a house where, if you brought something into it, you had to get something out of it. I have a storage space right now. I’ll go there and see a signed Duplex Planet book and I still feel this insane, intense connection to it. It’s tragic but somehow I feel this ridiculous pull to keep the artifacts I bought at the NYU bookstore. Digital photography has been helpful—I can see something and photograph it and that’s enough. I’ll be in the thrift store or at the garage sale, I’ll take a picture and I don’t need to own it.

Had you thought about being a filmmaker before you worked at Columbia House?

I went to NYU as an undergrad, but I was not a filmmaker. I had film major roommates, people who were in Tisch but I was a philosophy major. This moment came where I became obsessed with documentaries of every kind. I was going to Film Forum runs of like Frederick Wiseman films and the Maysles, but then also discovering artists like Sadie Benning and filmmaker Jem Cohen. I was devouring every form of nonfiction. In the early 90s, it seemed like a totally underexplored form. My parents gave me a Hi8 Sony video camera when I graduated from college, but said I was on my own if I wanted to live in New York City, that was when I got the job at Columbia House. I was still music obsessed. This was also a time and again but that was when you could live on the island of Manhattan in a bohemian way. You could pay 300 bucks live with a few roommates.

I thought, I am going to document [the job] and tell the story of it. It took me a minute to realize, Oh, there’s something happening here about my generation, which is I am being entrusted by this company to help them market to my generation because they can’t get the voice of it right. That was a big thing at the time. They so wanted the voice of the target demographic to help them sell it back to their own generation. So that was a sort of phenomena of that moment. At a certain point, midway through filming, I was like there’s something going on here way more interesting than documenting this institution. I was having this very coming of age post college experience in corporate America and it very much felt like The Office before The Office. The absurdity of work culture and the 17th floor versus the 19th floor and the suits and the creatives that was at play. It felt very screenplay worthy at the time.

Tell us some secrets about Ira Glass.

[This American Life] was a dream job. When I heard that show was even trying to become a TV show, I was like, OMG, how do I get considered to direct this? I got the job but the job was just to do a test tape. I knew that this was sort of like a once in a lifetime experience, so I killed myself and we made an entire pilot episode with almost no money and basically it ended up being the pilot episode that eventually aired. I knew that if we didn’t blow the Showtime executives away, they weren’t going to greenlight the series. So I worked for 6 or 8 months for nothing, but I knew this was one of those chances you had to just take.

I got to see how they worked, I got to sit in on their story meetings, I took notes on how they constructed stories and did their research. I was voracious in wanting to learn and understand how they did things because I was so in awe of this magical product that they made. I learned that they were relentless. Ira would burrow into every single story that he was working on himself, or help somebody else shape or sculpt, or work with a writer to extract their voice. Their work ethic was breathtaking: These people worked so, so, so, so hard and obsessively. I’m still living off the fumes of that experience creatively, personally, it was incredible. As a professional experience, I’ve never had that replicated, where you were doing something where the network did not give you a single note, didn’t bother you. [The network] loved what was being created.

Has the Flipside guy seen this movie?

Yes, Dan [Flipside’s owner] has seen my documentary. I had to send him a DVD because he is so anti-internet and has no online access. He does not have a smartphone, so we had to figure out a way to burn a DVD of it, which nobody in my immediate orbit had done in 10 years. So it took a fair amount of effort to get him to see it. I invited him to a screening in New York and it was on a Sunday. I called him and he said “Nope, we’re open today so I can’t go.” I was like, “fuck, dude, come on, just come to the city.”

Dan considers himself more of an archivist. Flipside is more of a museum. You don’t go there to find something you want. You go there to have your mind blown by like digging and pulling things out and being like, Oh my God, this sound effects record from 1972. It’s like this confetti pile of all this detritus from the 20th century that’s collected there, so the experience of shopping there is so special, but it is kind of gnarly, you get filthy, it’s cold in there. A certain kind of person who goes in there and is ready to dig and move things and make a mess. When you go to Station One, it’s air-conditioned, you can pay with your credit card or Apple Pay. It’s a totally different experience. There are fewer and fewer people who have the patience or energy to spend three hours rooting around looking for stuff in Flipside).

Have your parents seen Flipside?

Yeah, they came to the Toronto screening, I think they were momentarily terrified, but they got so much love after from everyone who was there and we went out for a big dinner after and they so enjoyed how people responded to them that it forgave some of their self-consciousness around what’s actually in it. My dad doesn’t love the soap stealing scene and my mom was complaining about how she looked and felt like she was too harsh toward Judd Apatow, even though that’s really how she felt. But I think now they are enjoying the experience of being included in it and they see it for what it is, which a bit of a love letter to them in it.

Looking back, it was so absurdly fun working there. Talking with like-minded people all day about bands and records. Obsessively reading zines and consuming any information I could about music. This isn’t really a skill but it was my first experience having a job that I was good at and felt effortless. I never noticed the time passing. I didn’t realize how much I was learning and absorbing … about how to run a small business, how to interact with people. I loved being there. I would often leave at the end of a work day with an armful of new records instead of my actual paycheck. It suggested that you could get a job doing something you loved. Which was a modest epiphany at the time! CF