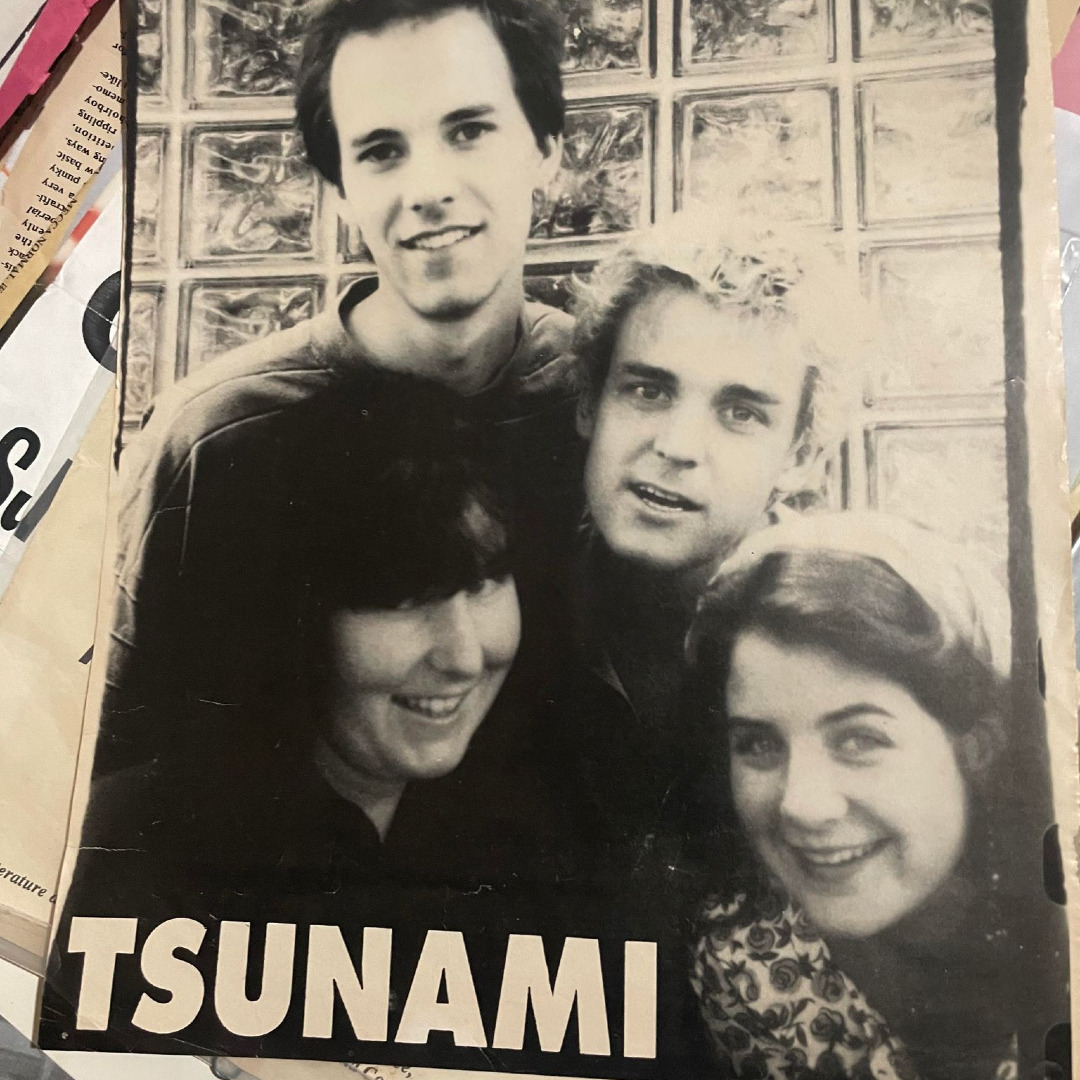

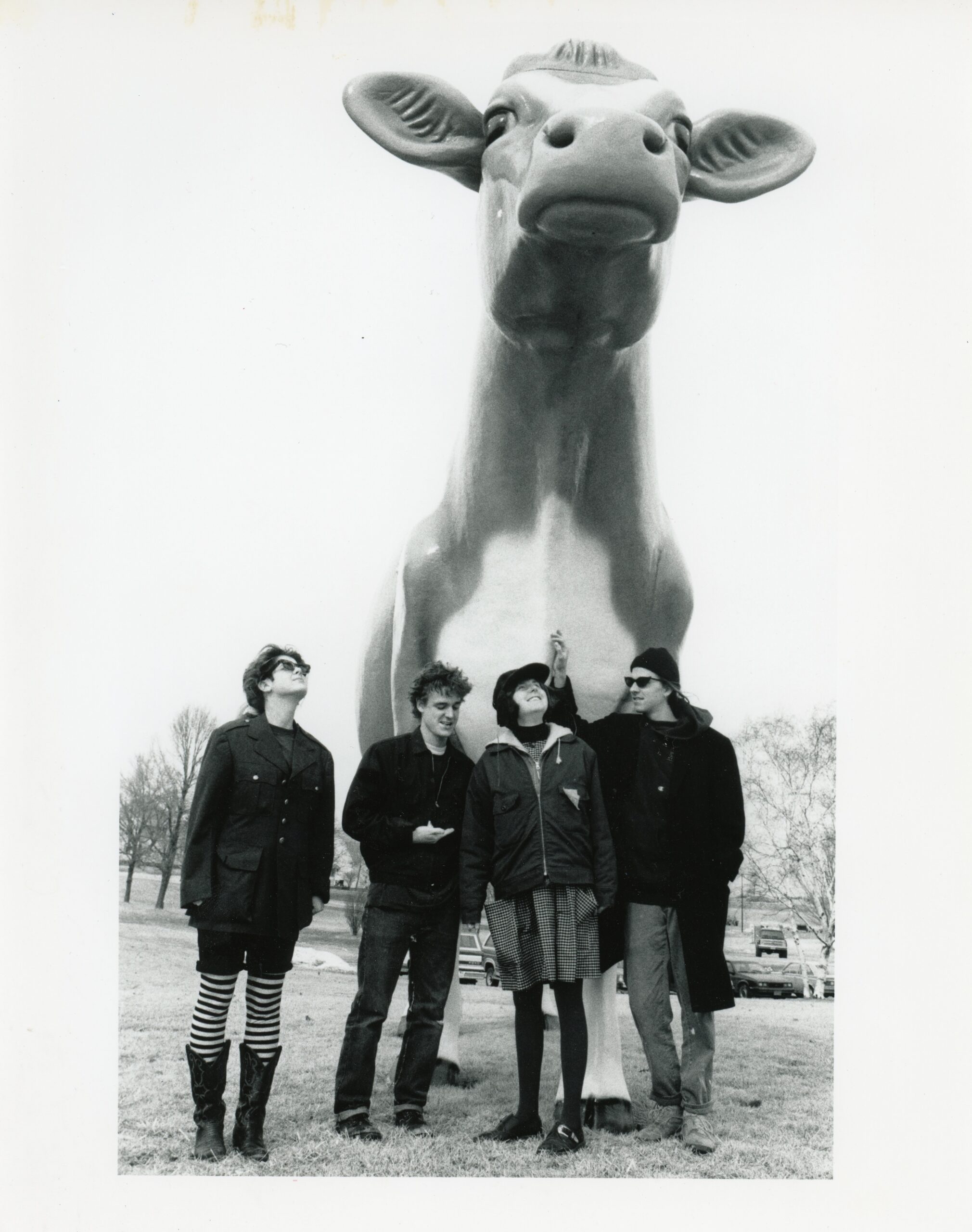

You chickfactor readers already know that Kristin Thomson and Jenny Toomey were very involved in the independent music world in Arlington/D.C. in the ’90s. Jenny cofounded Simple Machines Records with Brad Sigal and Derek Denckla, and then she and Kristin went on to run the label (with Pat Graham and Mickey Menard) and were involved with the Future of Music Coalition. (Our zine started around the same independent universe/era, and our festivals were surely inspired by their events.) Like many other folks at the time, I had a copy of Simple Machines’ guide to starting a record label, which made it seem like something we could all do (and many of us did!). Tsunami (which also featured John Pamer and Andrew Webster, among others) reformed in recent years to perform and have just released a big fancy box set of their music and are preparing go on a tour early next year with Ida. These two lifelong friends chatted with us recently about indie confessionals, mechanical bulls, and “shorting it up,” among other things.

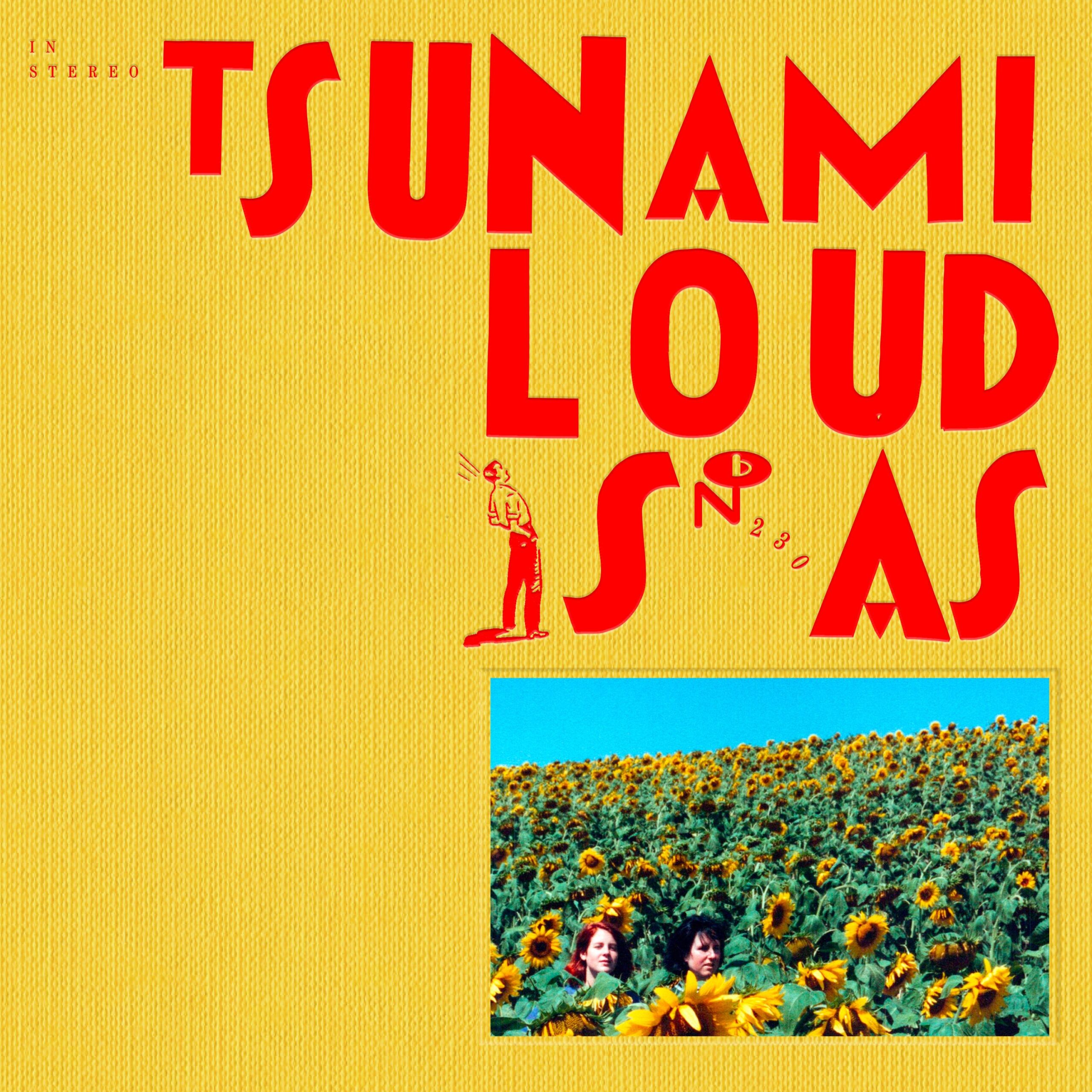

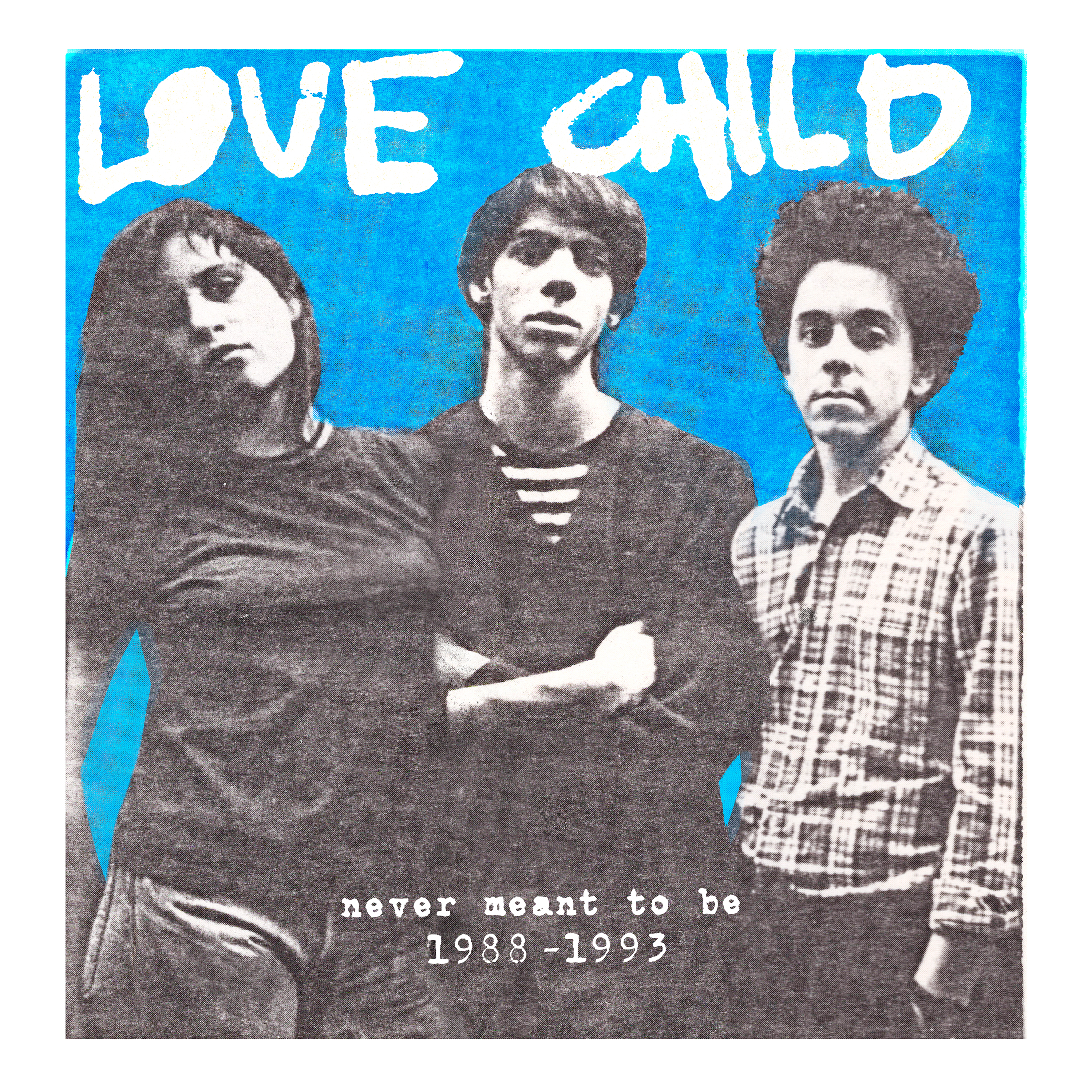

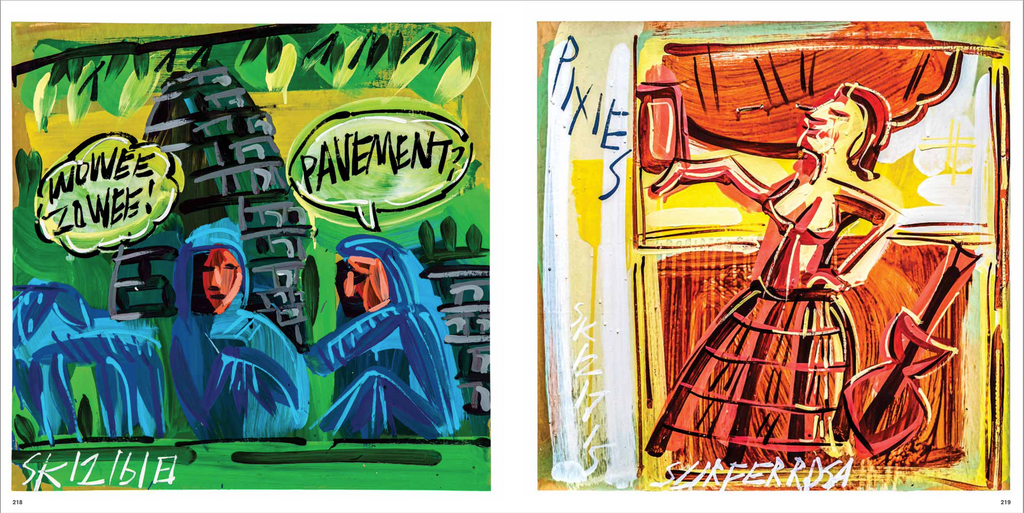

Hey nerds: check out Loud Is As, the new Tsunami retrospective on Numero Group: 62 tracks over 5LPs collecting together 11 7-inches, 4-track demos, 1993’s, 1994’s The Heart’s Tremolo, plus 1997 A Brilliant Mistake on vinyl for the first time ever.

Read our oral history of Lotsa Pop Losers

chickfactor: What did you guys do this weekend?

Kristin Thomson: On Friday night I went to see Duster, technically a labelmate. Curious to see them since I didn’t really pay attention to them when they were active in the late ’90s. Saturday I drove to Lancaster to see Jawbox, and they are a force to be reckoned with.

Jenny Toomey: On Friday night, I tested the makeup for an insane little joke unboxing video, which basically is me opening the Tsunami box set, pulling them out and throwing them to the side as if I didn’t care about them at all because I’m trying to get to the electric face mask underneath. When I put it on, it burns the word Tsunami on my forehead. So I was working with an actual makeup artist, and it took about 2 1/2 hours. I went out to drinks at the little punk rock club in town. Brian, my husband, who’s a journalist, was down in North Carolina. He got home Saturday. We have this huge CSA because we live in farm country, and I always complain to Kristin that I feel like I have another child, which is all the vegetables I have to find a home for in my stomach by the end of the week. So we did a lot of cooking and watching horror films.

Kristin: Baby Kohlrabi hanging out with you or something?

Jenny: We got Kohlrabi, which was in the share. We’ve also got a weird new vegetable, which is a mixture of broccoli and lettuce or something. How often do you say, “I’m 56 and I’ve tasted a vegetable I never had before”?

CF: Where do John (Pamer) and Andrew (Webster) live these days?

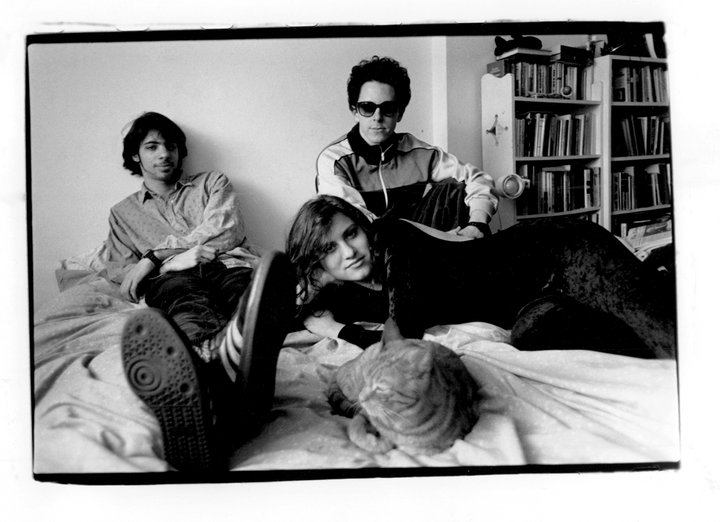

Jenny: John is a professional photographer and lives in LA. Andrew is a green architect with his own firm and lives near Amherst.

CF: What are your day jobs? Tell us about your pets, kids, hobbies, whatever.

Kristin: I am director of special projects at Media Democracy Fund, we’re an intermediary between the very large foundations and grantees that do work on everything from broadband access to fighting racialized disinformation. There’s a very small team, only eight of us, so we have a lot to do, whether it’s making grants and contracts or doing events or leadership development, building coalitions and things like that. My son Riley is upstairs, but he goes to Saint Joseph’s University and works in the box office at a venue in Philly. Jenny could talk about pets.

Jenny: I can. One of them is currently trying to interrupt our interview. He’s our new rescue, Iggy. I’ve worked at the Ford Foundation for 16 years. I started a technology portfolio where we support organizations working to put rules in the internet environment to protect the public ….

CF: That sounds easy.

Jenny: You don’t know the half of it. Not only have we not managed to do that, but for many years, I watched as we ignored what was coming. Few of my peers thought what was happening in the tech space was all that important. They were all doing social justice work, so they didn’t care about “fancy technology issues,” … and I’m like, “Oh, no, it’s coming for you!” And they’d be like, “I’m not interested, and I don’t have to be.” And I’ve been like, “Oh, no, get ready for the horror film that is going to be your portfolio.” I’ve been working with the president of the foundation because he immediately got it—how dangerous tech was and all the areas we cared about so he’s kept me around. For the last five years, I have focused on building the field of Public Interest Technology. This boils down to training technologists in a more cross-disciplined way so they’re more effective in environments beyond the private sector. We’ve also been creating pathways for them to go into government and civil society so the next generation of technologists can tell their parents, “I just got this costly computer science degree, but it’s OK, I’m going to go work in government, and there is a role for me, and you don’t have to be scared that I just wasted all of that money.” I’m leaving Ford at the end of this year, and Kristin is also leaving her job. So we’re basically just Thelma and Louise-ing the next year.

CF: That’s awesome. Did you come from musical or artistic families? What were you like as teenagers?

Kristin: The thing that people find most interesting is that we moved a lot. My dad was in corporate real estate, so there was bouncing back and forth from Canada to the United States. You get used to moving and starting fresh with new people and new experiences. I took regular classical piano lessons growing up, but I was listening to music and going to shows and getting more interested in bands mostly by the time I was in high school when you could maybe go to a show in some weird all ages space or listen to music based on what other people were listening to in your very small school, things like that. By the time I got to college, I was part of the college radio station at Colorado College—KRCC—and was part of the concert committee.

Jenny: With regards to music, we always had music playing in the house. As soon as they came home, they put on the turntable. In junior high, I sang in a professional choir called the National Children’s Choir, which Amy Pickering and Kate Samworth were also in. It was like three practices a week, a month of summer camp and dozens of performances during the holidays. So I sang a lot, but it wasn’t until I was in college that I got into a band. I was such a punk rocker in high school. Many punks went to BCC (Bethesda Chevy Chase high school), and I was lucky to make friends with the Bloody Mannequin Orchestra guys, who would drive me to the punk rock shows in DC. Once that started, I lived from show to show. It became like the most important thing to me. Then I got into Positive Force, which also put on tons of shows. Still, I didn’t start thinking I should be in bands until Dave Grubbs and I were friends in college at Georgetown University, and he asked me, “Why aren’t you in a band?” And I hadn’t thought about it, probably because there weren’t that many girls in bands, and I didn’t see the pathway, but once he asked, it was just like, “Oh my God, sexism, there it is!” I’m doing an undergraduate degree in sexism, and I’m obsessed with punk, but I don’t know I can be in a band. I called my friend Derek Denckla and said, “We should be in a band.” That’s how Geek started, and that eventually led to Tsunami.

CF: When you look at a lot of those old punk photos from DC, it looks like all men in a lot of them. I know there were women there.

Jenny: There was a time before that, like before Minor Threat, where it was a smaller scene, more new wave and weird and I think there were more women in bands then. That’s why Dave Grubbs could ask me that question: Louisville also had a weird, small scene where Tara Key was one of the most influential musicians, and everyone looked up to her. So it didn’t seem odd. But it wasn’t until I was in college, or maybe close to it when I was in college, that Fire Party started. And right then what I couldn’t previously imagine was happening before my eyes.

CF: What was your first concert? The first record you bought?

Kristin: I definitely know the first record. I bought the B-52s yellow record with my own money in probably 7th grade and I loved it. I mean, I must have almost worn it out playing it. I loved it so much. I think the first show I actually saw was the band Chicago, but it was free because they were playing at the New Mexico State Fair. And I just wandered through the crowd. You know how Chicago named lots of their albums numbers? They were on like #19 or something and I was like, “a band can have enough music for 19 records?” That’s amazing. I think the next one was Tom Petty.

Jenny: I don’t remember seeing a lot of big concerts. The first punk shows that I went to were 9353 shows. They played all the time, at least once a month. I was obsessed with them. They are entirely undersung. Before I went out to shows, Bloody Mannequin Orchestra would play at the BCC talent show, or I would go over to Whitman and Geoff Turner from Gray Matter would be playing at the Whitman talent show. It wasn’t until the late ’90s when I started reviewing music for the Washington Post that I went to large concerts. And I think that’s the only period when I did that. Though I remember I got tickets to see the Michael Jackson Victory tour in high school. But I don’t remember going to many big shows or paying any attention to those types of bands. I never listened to The Beatles to even know what The Beatles were.

Kristin: Now you can listen to The Beatles and like them. It’s a whole new thing for you.

CF: What was Arlington like when you guys were there? It was so chill then. Now it might be the most expensive place to live in the D.C. area.

Jenny: When I went to Georgetown, I really didn’t want to stay in the dorms. So I didn’t most of the time. I lived part-time in a group house with some of the Beefeater folks, Nicki Thomas from Fire Party and some other punks, but by freshman summer, I was staying at Positive Force. I didn’t have a car, so I would ride my bike back and forth to Georgetown from Arlington, and at 8 or 9 p.m., the streetlights would just start blinking yellow. It was that quiet a town. The streets rolled up when Sears closed for the night. Simple Machines Records started in Positive Force house and operated there for many years until we felt the need to start our own house.

CF: How many people lived there?

Kristin: About 10 people at any given time.

Jenny: That would be the worst-case scenario. But you know, people had sweethearts, others would crash at times. The Positive Force meetings were held in the living room. At a certain point, it felt like I’d lived there too long. So, no shade on folks we still love from the house, but we were ready to start a new chapter. I remember when we first moved to the first Simple Machines house, we’d moved in the springtime, and there was a cherry blossom tree blooming in the front yard, and I had my window open, and it was quiet and there were no dishes in the sink, and I just felt soooo happy.

Kristin: I mean, the other part of it is like that we were within a 4-minute car ride or maybe 15 minutes on your bike from Teen-Beat house, Dischord, Dischord Direct, John Pamer’s parents’ house, where we practiced at the beginning, from other bandmates. So there were so many things. Yes, Mount Pleasant had named houses, lots of people lived there, but there were similar lots of connective tissue in Arlington.

Jenny: I’m going to say that if it’s the most expensive place in the world, Kristin, your father gave us bad advice when we were trying to get that house.

Kristin: That’s right. We were like, should we buy it here? He did say don’t buy it. It would have been worth a lot of money. It is sad to say that there were three different houses we lived in. None of them are standing anymore. They’ve all been replaced. Knocked down and something else put in there.

CF: I bet Cynthia Connolly documented it all.

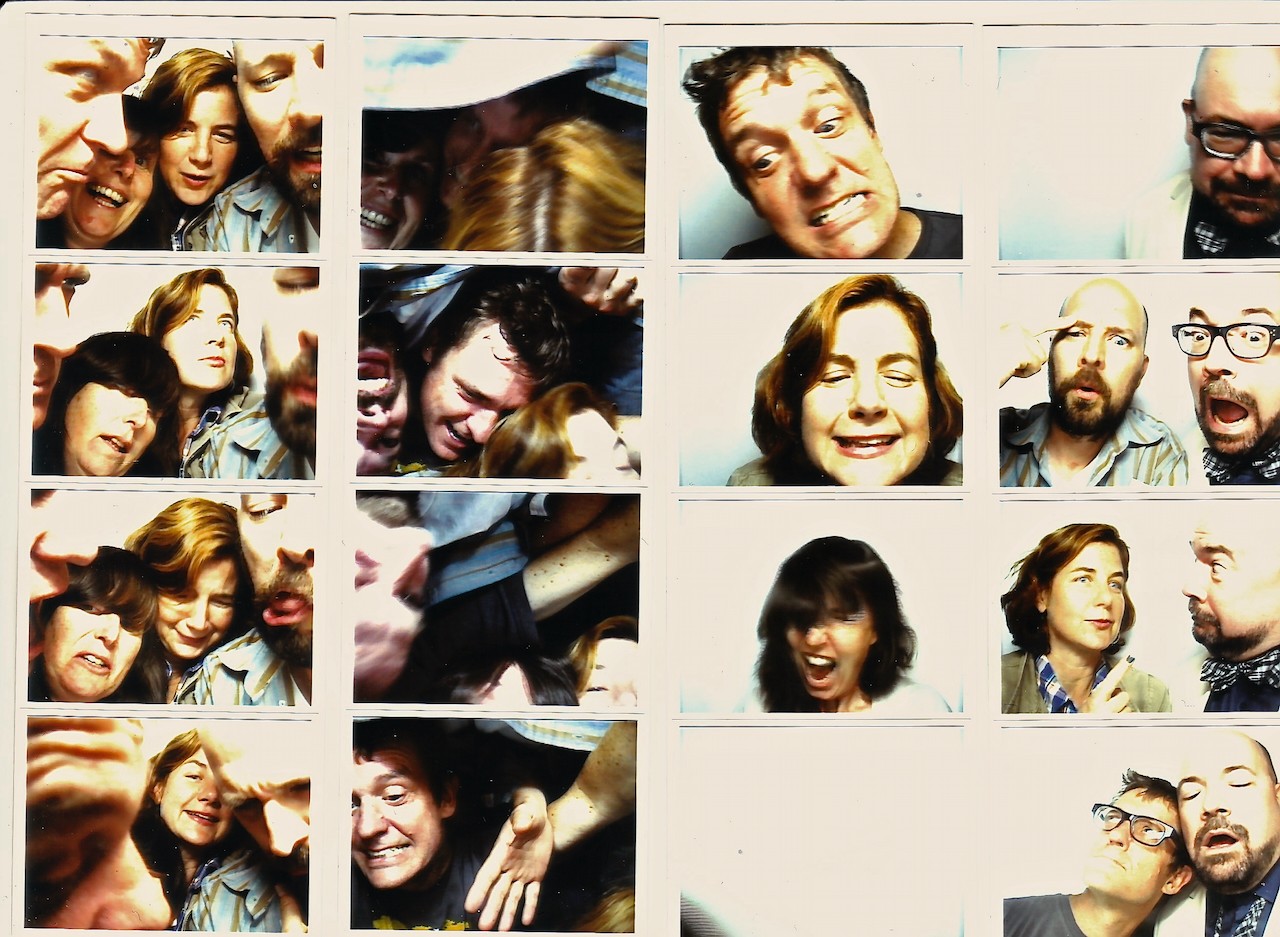

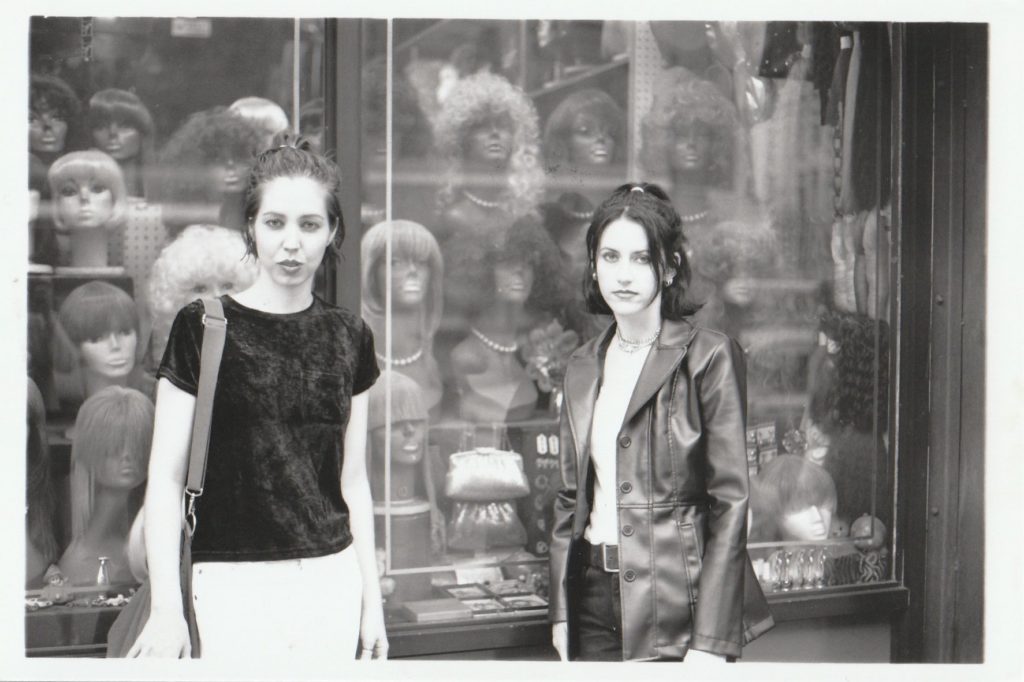

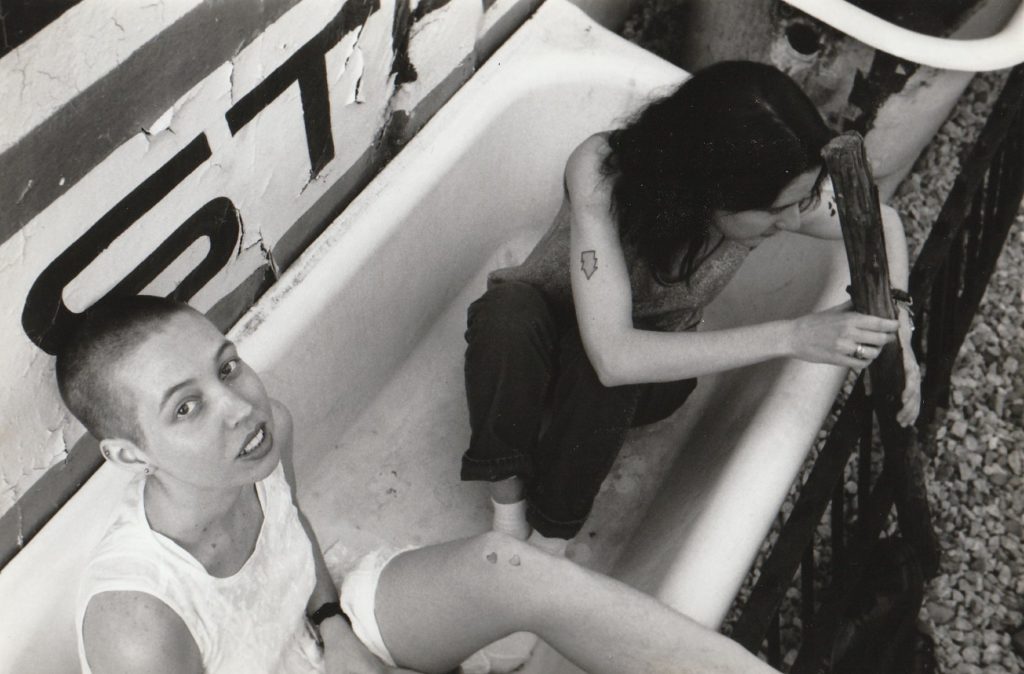

Kristin: And our housemate Pat Graham, who took tons of photos. Pat is amazing. He took tons of Polaroids at the time.

CF: Do you have any stories about being involved with Positive Force, events or actions?

Jenny: How long do you think you lived in the house, Kristin?

Kristin: Maybe two?

Jenny: I was there at least five years, if not more, because I also spent the summers in the first Positive Force house, which could get to like 15 inhabitants. When another house closed down, they just moved everybody into the basement if they needed a place to stay.

Kristin: The show that was the most high stakes in my mind was during the March for Women’s Lives. It was April 1992 where we had Fugazi play two nights and one day it was Bikini Kill and L7 and the other night was Scrawl. I have the flier somewhere. I was already working at NOW and I thought it’d be a great way for people to be attracted to D.C. to come to the March, and also be a fundraiser for Planned Parenthood. But there were also attacks on abortion clinics in the DC region that were timed with the March. So there’s high stakes clinic defense stuff going on, we were raising money for Planned Parenthood—this is where Pat took those very famous photos of Bikini Kill, the one where she’s sitting on the ground—it was a very intense show. And if you read Kathleen’s book, it was an intense day for her too. We pulled it off and it was just very intense.

Jenny: For me, some of the earlier Positive Force things stick more. Events like the Dupont Circle Festival were formative. I was underage; I was too young to get a permit, but somebody older than me went to sign the documents. And we had to do everything ourselves, like building the stage. I took a bunch of bad photos of that Alternatives Festival, and it’s just so interesting to see the range of performers.You had black poets and then Julianna Luecking and then the Morning Glories and with Peter Hayes, and I think Fugazi and the Hated and also my band Geek played. Back then it was easy to do a free outdoor festival. All you had to do was imagine what you wanted, and folks would come together and make it happen. I did something similar at Georgetown. I asked Jeff Nelson to do a poster for it. He silkscreened this very complicated poster because Jeff Nelson has a predilection for very complicated things. He drew all of these people pulling on a rope as one side of a tug-o-war, and he asked Ian MacKaye to do all of the poses so that he could get the musculature right. But if you look at this poster, which I still have, it’s this beautiful multi-color screen print of 4 Ians pulling … like a woman Ian and a black Ian and a long-haired Ian.

Kristin: I also liked the stuff that was very routine, like that we were on schedule for, like, spending the night at the Community for Creative Nonviolence to cover for the staff. So you’d show up at midnight and stay till 5. It was a lot of just making sure there wasn’t an emergency, but the constant working with the Emmaus Services for the Aging to help. A lot of just community service stuff and you felt good helping.

Jenny: It’s a natural tendency for people to be creative and help one another. It’s so strange right now because the media and misinformation are constantly cultivating our distrust of everyone. But even so, over and over again, when there’s a crisis like a hurricane or a flood, the first thing that people want to do is to help each other. And I wonder why it’s hard for us to remember that outside of crisis.

CF: Let’s talk about Simple Machines. What were some of the challenges, proudest moments or biggest achievements? Funny stories?

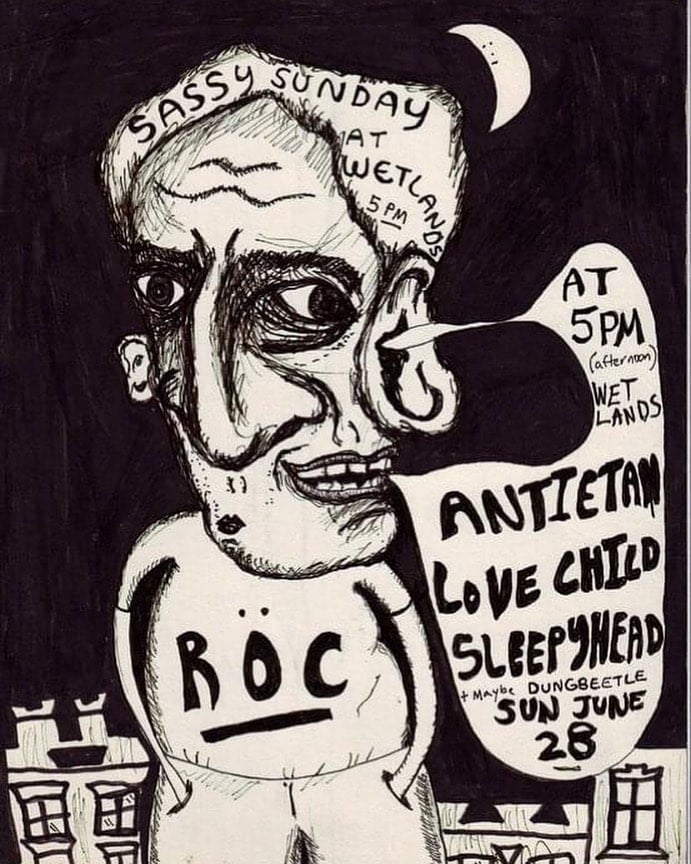

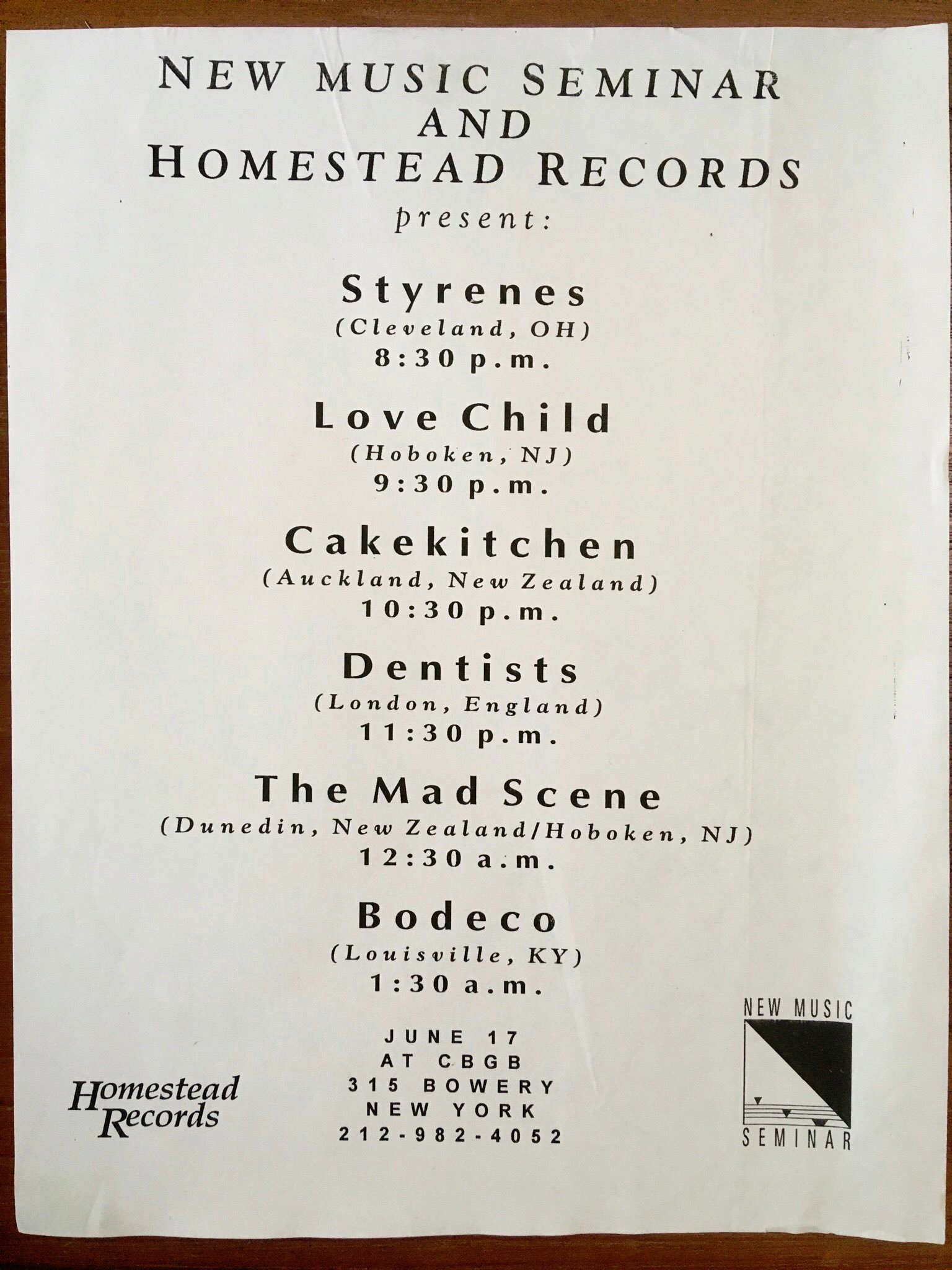

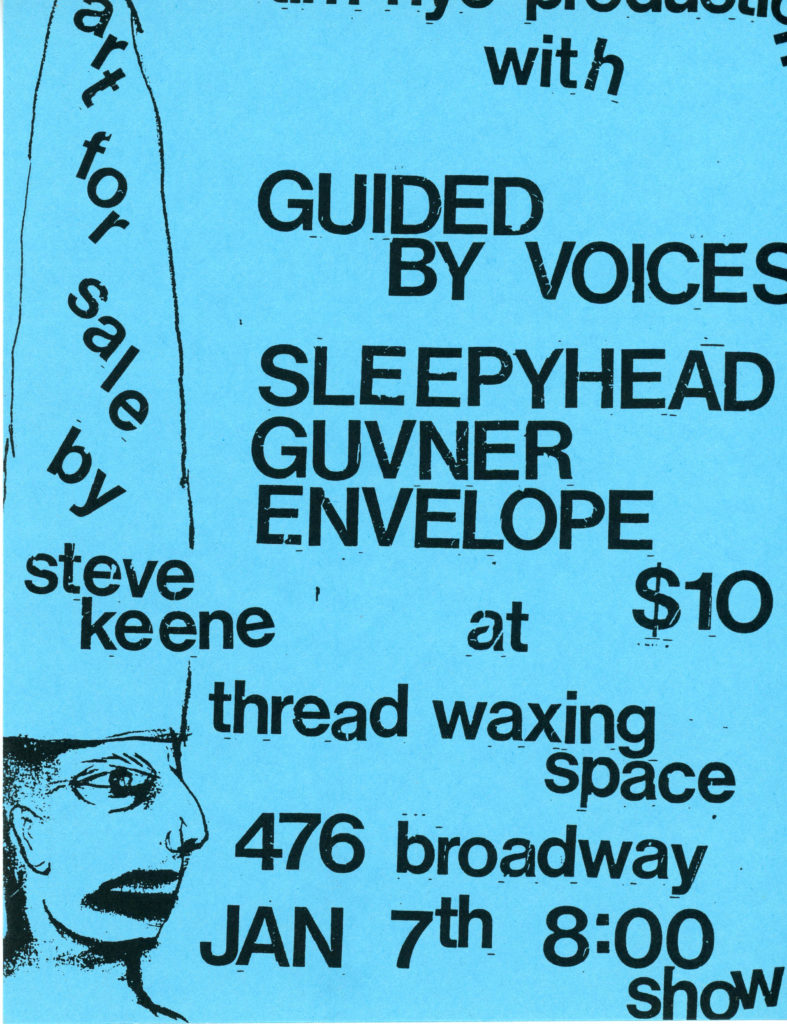

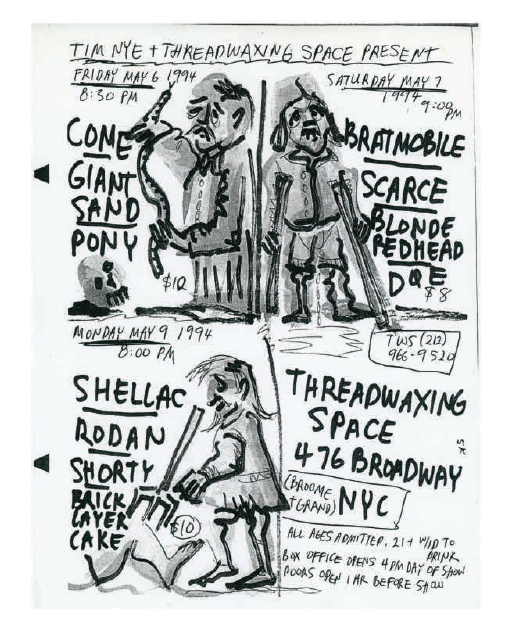

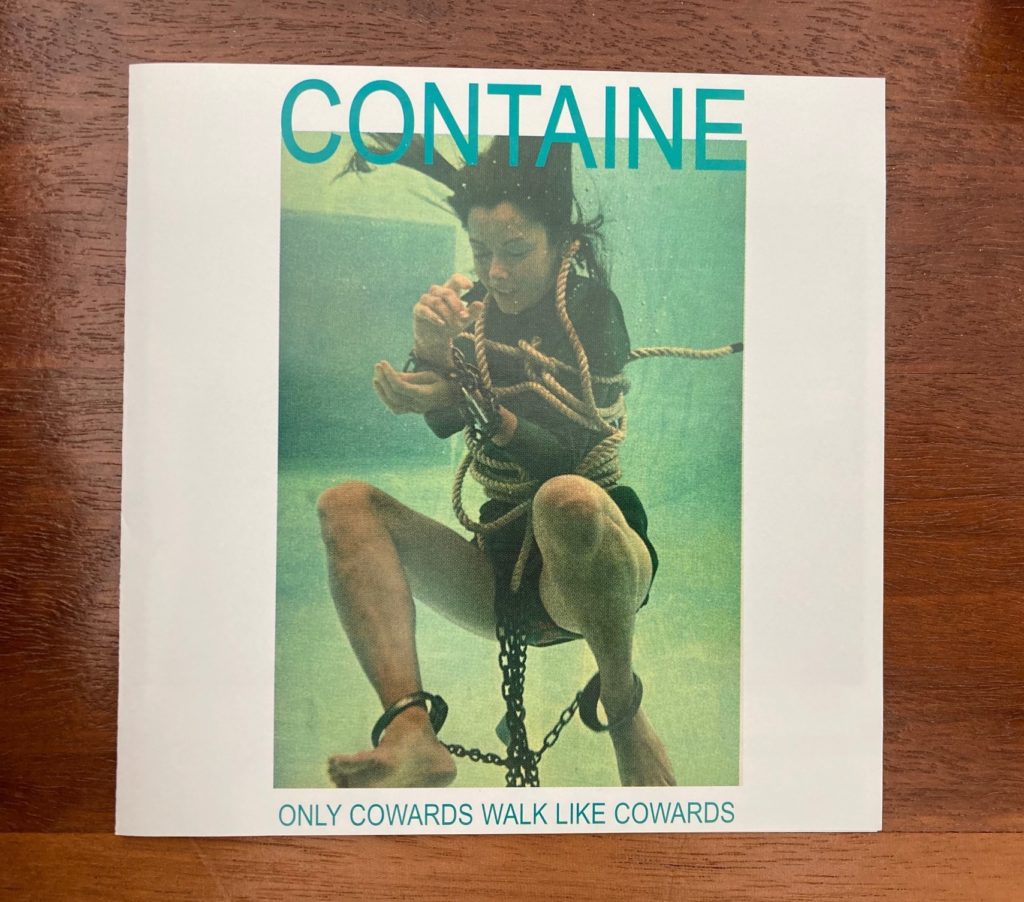

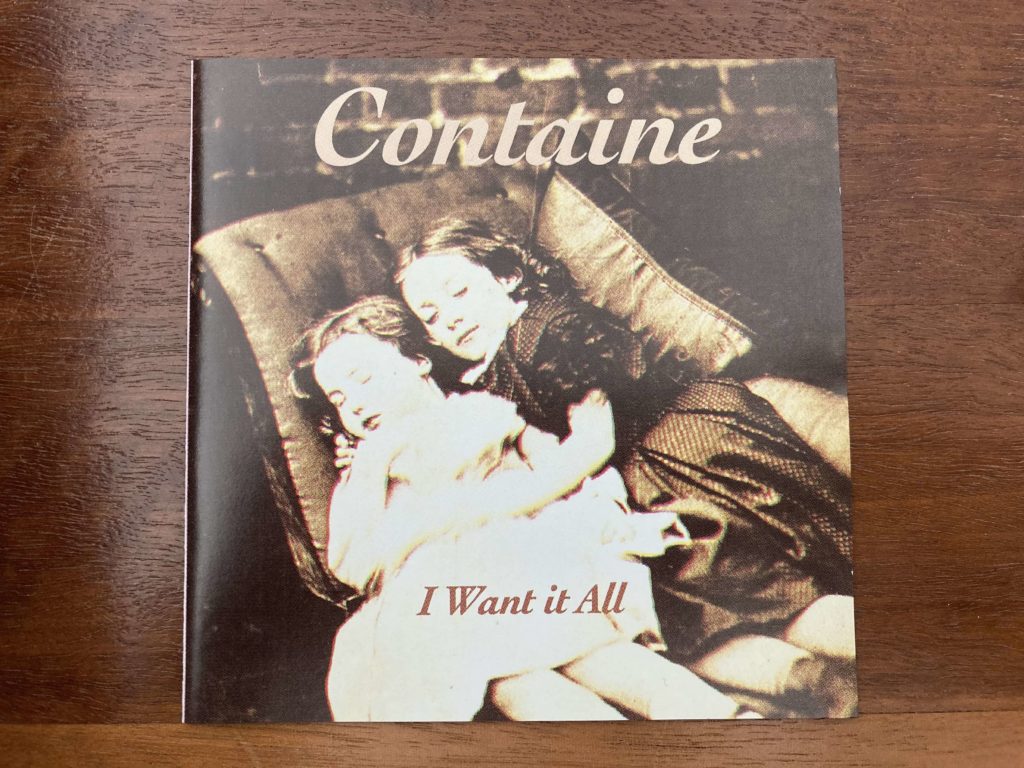

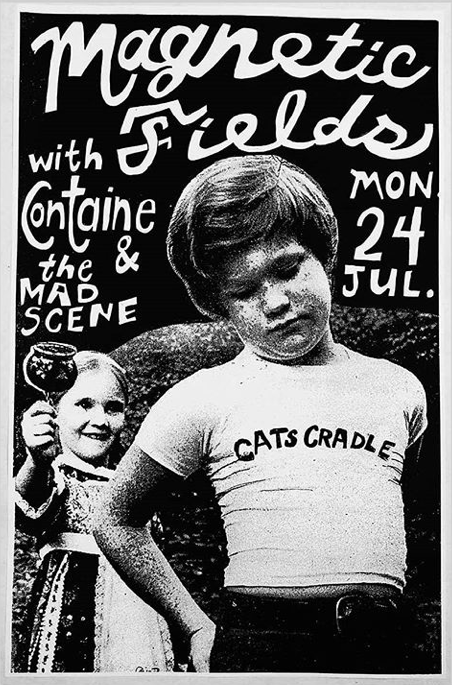

Jenny: Every element of it was fun, even the end. The gift Kristin gave me, though it initially felt like a punch in the stomach, was when she said, “If we keep working this way, I’m probably not going to love it anymore.” She was right, so we decided to end on a high note. There were moments near the end where it felt like a slog. It could be overwhelming at times … mostly I’m proud of everything. I’m proud of the weird cassette series that we put out. I’m super proud of the music that we put out … I mean, we put out Scrawl records! Come on, how lucky is that? All the events like Lotsa Pop Losers, Working Holiday, or the final Kick The Bucket funeral show. I particularly loved just putting together thousands and thousands of seven-inches and sending them out.

Kristin: Working Holidays fest had the kissing booth too.

Jenny: Kristin, you’re forgetting, though, it wasn’t a kissing booth, it was a confessional.

Kristin: I stand corrected.

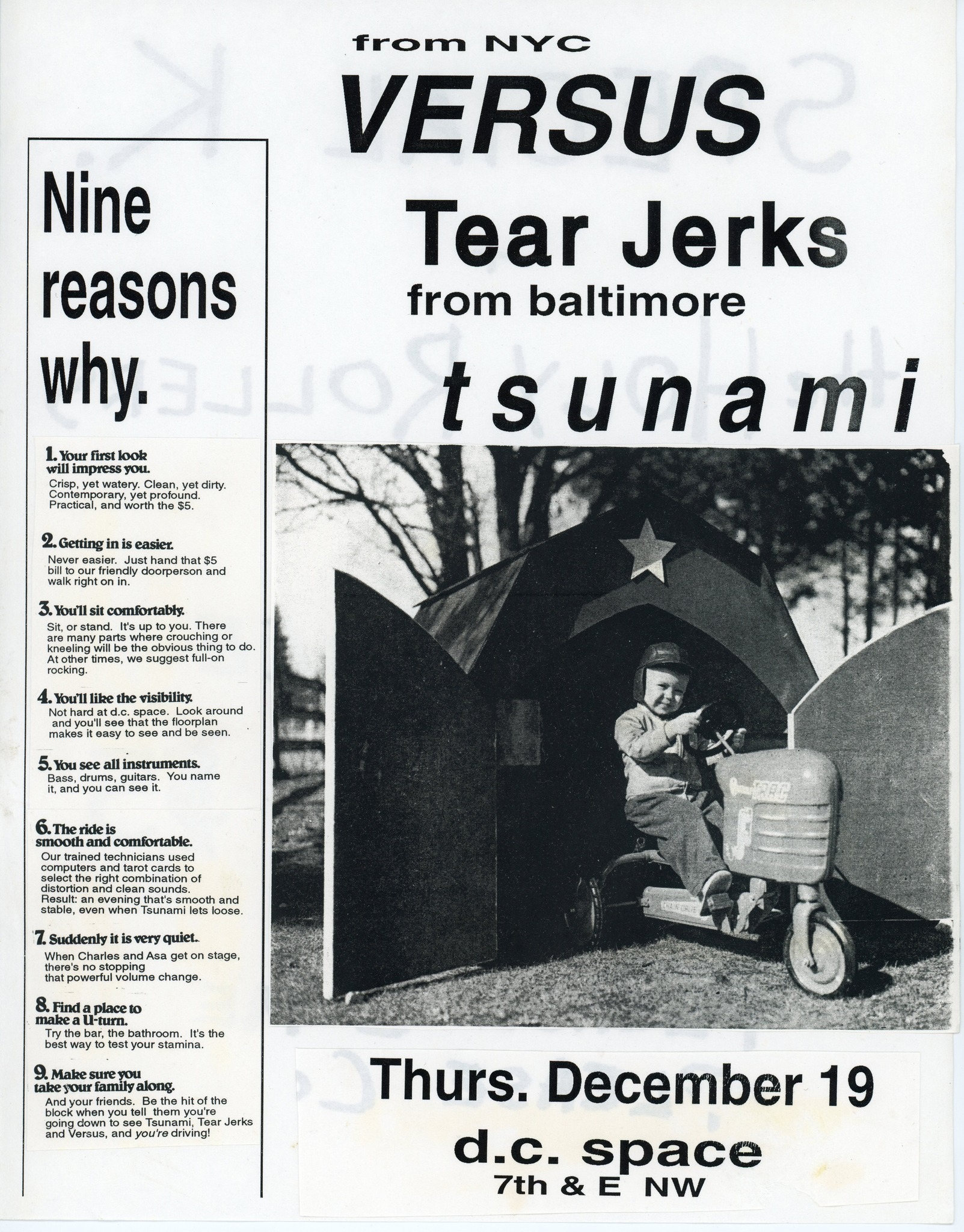

Jenny: Different band members held court on one side while audience members sat on the other side and confessed punk rock sins. We’d announce from the stage, “Richard from Versus will be in the confessional between Eggs and the Coctails’ sets.”

Kristin: During Working Holiday, we had a ghost postage situation. Franklin Bruno wrote a song about it. Because we were sending out so many 7-inches routinely, like every other month, here goes 800 packages, we had this standard Pitney Bowes you’d rent and you have to get it refilled at the post office. This is old school, people. You pay some money and they’d reset the numbers on the dial so you had X number of hundreds of dollars of postage. Well, the lady at the post office who we probably saw every other day by accident gave us not $500 but $5000 of postage just by clicking the wrong dials. We realized the error when we got it home, but we didn’t say anything so we used the postage for like 8 months. At the very end when we had no dollars left and we had to take the machine back in.

Jenny: We shouldn’t have done that. We should have just said it was lost.

Kristin: But we went back and it was the same postal clerk who in a panic realized that there had been an error. And I don’t know if she recognized in her handwriting or whatever, but she was like, no, you owe us $4500 and there was no getting around it. We owed them $4500, which we paid and I can’t remember how.

Jenny: Jim Spellman loaned us the money. “Moneybags Spellman.”

Kristin: Adventures in mail order. Otherwise one of us would have an idea, we would rev each other up like, “well, what if we also had a birthday single?” “oh, wait a minute, how about we do a special stamp?” and then … ideas became like AHH and then we would do it.

Jenny: Kristin and I trigger each other’s obsessiveness around this stuff. And it was funny because when we lived in Positive Force house, I’d have to walk through her bedroom to get to my bedroom, which was a freezing sleeping porch. I’d walk through the upstairs defunct kitchen (which Simple Machines turned into our office) and through her bedroom to get to mine. So if she heard me doing Simple Machines work in the kitchen, she’d get out of bed and come out and work, too. And if I heard her going into the kitchen to work, I’d get out of bed and work. So it was this very unhealthy but productive relationship.

CF: Very strong work ethic. (We talk about music categories and getting lumped in with certain artists and how indie rock is kind of a pointless term that doesn’t say anything). Discuss.

Kristin: Indie rock isn’t really the sound. It’s more like the hierarchical status of the band, like they’re not signed to a big label, they’re not a pop star, all those things. So it seemed like an easy way to say like, well, they exist in this layer, even if it’s like everything from the Tinklers to Tar. There was a giant swath of bands that were on decent sized indie labels that played guitars. It’s a catch-all that doesn’t really describe the music.

Jenny: We talked a lot about this on Tom Mullen’s “Washed Up Emo” podcast. For people who believe in emo—and who am I to deny that emo exists?—there have been layers, generations, and waves of music on which people have written dissertations. But being someone who was in the town watching the punk rockers before there was that terminology, it seemed like a strange joke, right? It will always seem revisionist as opposed to factually accurate. Though, of course, it is both. It’s the same thing with riot grrrl. When people put a name on a genre … tying a band to a specific type of music … I don’t mind if it’s helpful for people to encourage them to try it out … but when this happens, it’s usually because somebody is on a deadline. It’s a bit of a shortcut.

Kristin: These days it’s almost like a drop-down menu of particular genres and like a UX on something being uploaded.

CF: A lot of the stuff that we all cared about back then—integrity, creative control, feminism—still matters because it’s ingrained in our DNA, but feels like a luxury at a time when it’s so hard for bands to make any money. How have things changed for you? Both of you have proper jobs so it’s not like you have to take time off from bartending or whatever to go on tour. What were some of the challenges that came along the way?

Jenny: One of the reasons Kristin raised the concern about whether we should continue the record label was because it got to a point where we couldn’t do anything well. We couldn’t work an interesting day job because we had to take chunks of time off to tour. We couldn’t tour enough to cover all our expenses because we had to be home to get the records out. We found ourselves in an impossible scenario. Some labels solved that problem by getting a financial partner, selling the label, or bringing someone in. The things taking up a lot of time at that point were press and promotion, which had little to do with why we wanted to put the records out in the first place. Sometimes people tell us, “It’s so cool that you didn’t sell out.” But let me tell you, there weren’t a lot of buyers. And of the people who took deals, there weren’t many great successes. I may have felt a twinge of jealousy when a band got a lot of attention, but anytime you got close to these major label people, you could see these relationships were pretty transactional. Even when I was on 4AD, the folks were nice but they’d always talk about music that “was going to happen” or music that was “over”. Everything was rated in this flat commercial binary. In the year that I got a salary from 4AD and didn’t have to work a job, the whole process killed the joy of writing music.

Kristin: I wanted to insert something in the record so we don’t forget it later because we’re sort of in this category. While we were busy on tour with Tsunami—especially as we did fewer sort of elaborate projects involving many bands like a Working Holiday series or the Machine series, and it was like we’re helping the Raymond Brake or Scrawl or Franklin Bruno with the actual record—that was when it became more challenging for Tsunami to also put out records and go on tour because we had responsibilities. Pat Graham ran our mail order, Mickey Menard ran our distribution, and did tons of bookkeeping. So, when we were on tour, they were often there keeping everything going.I also think we should mention that I was not around at the beginning of Simple Machines; it was Derek and Brad who started it with Jenny. Because we’re talking about this moment where we were like, I’m not sure this can work anymore because how can you balance out all these responsibilities and do it well? Because both of us are very driven to do things as well as we can and not to blow stuff off. So there were a lot of things piling up that we were responsible for, and we had to make our decision with the label. We were trying to be responsible for the bands that were around us to make sure everybody was whole.

Jenny: It was also a good time to take stock. Some of the SMR bands were getting major label interest and were beginning to leave, and we wondered, “are we going to replace these bands with other bands? Are we doing this to be a label, or are we doing this to help our friends?” And at a certain point, we realized we were ready for that next challenge. I was excited about doing the solo music—Liqorice and the Jenny Toomey stuff—and starting afresh and being in a band without carrying around all the other stuff. So, there were things we were giving up, but there was other great stuff we were getting. Kristin was getting to live in the same city with her husband Bryan, and to start that life, I was getting to move out of the group houses and work on new music.

CF: The DIY spirit, support and camaraderie were some of the great things that came out of D.C. and Arlington and the East Coast scene.

Kristin: Yep. It was nice to go on tour and meet bands or pass through scenes who had similar cohesiveness to them. There was obviously a lot of stuff going on in Olympia, WA, but there were things going on in Portland and there were things going on in Chapel Hill. It was very fun to go even brush past some of those other scenes and see what their lives were like or play shows or whatever it is.

Jenny: And that gets to a question you were asking before about genre. We came out of punk … earnest but also silly. The label started a year before the Geek tour with Superchunk and Seaweed. So, in the beginning, there were DIY and indie labels, and then there was this punk rock/young rock kind of thing. But we really came into ourselves when we met bands like Versus, Small Factory, Velocity Girl and, of course, Unrest. That was the beating heart moment of what we were doing with Simple Machines.

CF: Did Tsunami have any preshow/postshow rituals? Special elixirs, backstage snacks?

Jenny: When we toured Europe, we had a rider that was a little bigger. John Pamer put Dr. Pepper on it, which we got maybe three times. We asked for postcards and stamps, which we would get every once in a while.

Kristin: Who was it who had tube socks and batteries?

Jenny: That was the Butthole Surfers. They would come into the venue and refuse to load in. They’d say, “Where’s the tube socks?” And they would peel their socks off, leave them on the floor, and put the new socks on.

Kristin: We didn’t have any preshow rituals. Not really, no. We were like, “there’s 75 people here, let’s stand in the front row really closely”. It became kind of a habit where if you’re not playing, you’re in the front row to support the other band.

CF: Did Tsunami have any stagewear rules? Were shorts allowed?

Jenny: There were a lot of shorts. I remember the Nation of Ulysses was against shorts, but Tsunami shorted it up!

CF: You know it! Velocity Girl too.

Kristin: She always had great outfits and still does. Jenny, you had a pair of those classic D.C. shoes, like the canvasy ones that had the ridgy sole and if you stepped on your Rat pedal, it would get stuck in the ridge. We would swap shoes sometimes. So I would wear your shoes and you would wear mine.

Jenny: We wore lots of thrift because we love thrift shopping. I loved 40s dresses … I dreamed in gabardine and rayon. Unfortunately, I can’t get into any of them anymore.

Kristin: There was that amazing thrift store in Minneapolis. What’s it called? Deadstock. Ragstock. But there were times where we would thrift in the afternoon and so we would sell the merch, put the thrift stuff in the merch box and ship it home or just bring it home with us. And we come home, we’re like, there’ll be like a merch box full of thrifted things.

Jenny: I remember on that first Beat Happening tour in Waukesha, WI, Pat Graham took us to an enormous thrift store, and there was a girl in front of me in the aisle who had like an armful of fabulous dresses, and I was like, “Shit, we were 10 minutes too late!” But then, even though I was following her, I got an armful myself. It was so rich back then, and those stores were a very strong argument for the Midwest to exist.

CF: So what about your songwriting process? How did that evolve over time?

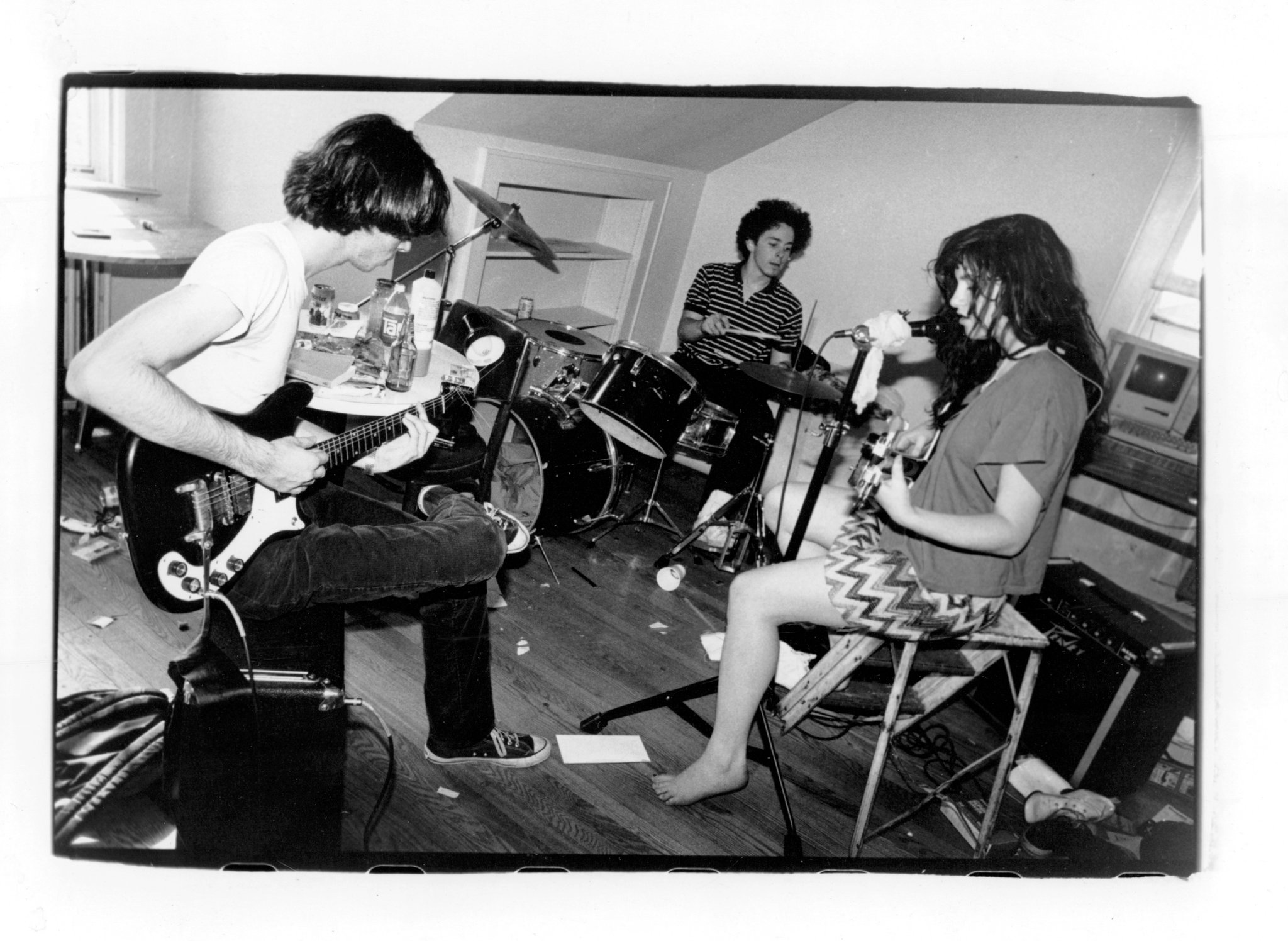

Jenny: Our first set of songs were in-jokes, funny, and fast. Bricks inspired us; they wrote their songs in 15 minutes, which is great. Kristin had never played guitar, I had banged a guitar with a stick in Geek, and Andrew had never played bass. We had a lot to learn. As we developed, the music began to reflect what we were experiencing: sexism in the scene and how mean people are to each other, crushes, workload and the press. The last record critiques how everything’s going, the vultures circling the independent music scene, and the gatekeepers and the people making less interesting choices, normalizing a kind of powerlessness that didn’t seem like what inspired us. We write our songs individually. We’re not a jamming band. And then we just work out stuff together in practice. It was really, really fun when we played at John’s parents’ house. We could play a couple of times a week, and because our brains were young and agile, we could learn things fast. Also, we were touring all the time; we’d get notions of new songs in the van, practice at soundcheck and then unleash them on the world.

Kristin: The lyrics have stood the test of time and I don’t know if it was just coming out of your journals or if you wrote, wrote, wrote, edit, wrote, wrote. Did they come fully formed or were they heavily edited?

Jenny: A few songs come fully formed. Most come as a feeling and shards of an idea that require a lot of sanding and reorganizing. I had a really difficult time remembering what was happening where, with whom and when. During Simple Machines, I was writing in my journals all the time, but looking back it was all crushes or bitching about something and clumps of confusing lyrics. Slogging through those volumes 30 years later feels like translating from a forgotten language. And it’s funny because I had breakfast with Ian recently, and we talked about all his archiving work. He figured out how to avoid ending up with useless journals like mine at an earlier age. He said he had a journal on his first tour of the West Coast. He saw all these punk shows. Instead of documenting them, he just wrote about how he missed Cynthia and how sad he was. And then, when he got home, he was like, “This is useless. I have to be more disciplined in my journal. What did we do? Who did we play with? What was the venue? What were the dates?” My journals have none of that which is incredibly frustrating, but I’m glad to have them because I still have access to the emotions, however gauzy and I can see how many different projects were happening simultaneously. So there are Tsunami lyrics next to Grenadine lyrics next to Liqorice lyrics, next to tour dates and production ideas and my Kinko’s work schedule, and it was all happening at the same time.

CF: Tell us about your friendship and how it’s evolved over the past decades and how what you’ve learned from each other?

Kristin: We’re like the Wonder Twins. Once we activate, we have a lot of additive power because we are both good at different things but they complement each other. I really like logistics and spreadsheets and being organized and all that stuff. I think we’ve been lifelong friends because we not only have shared values, but also have a way we can work together to make something even bigger than ourselves than the two of us. Or even bigger than the group that we bring together to help us do something else. I’ve learned so much from being your friend. I’m always learning every day, there’s something new.

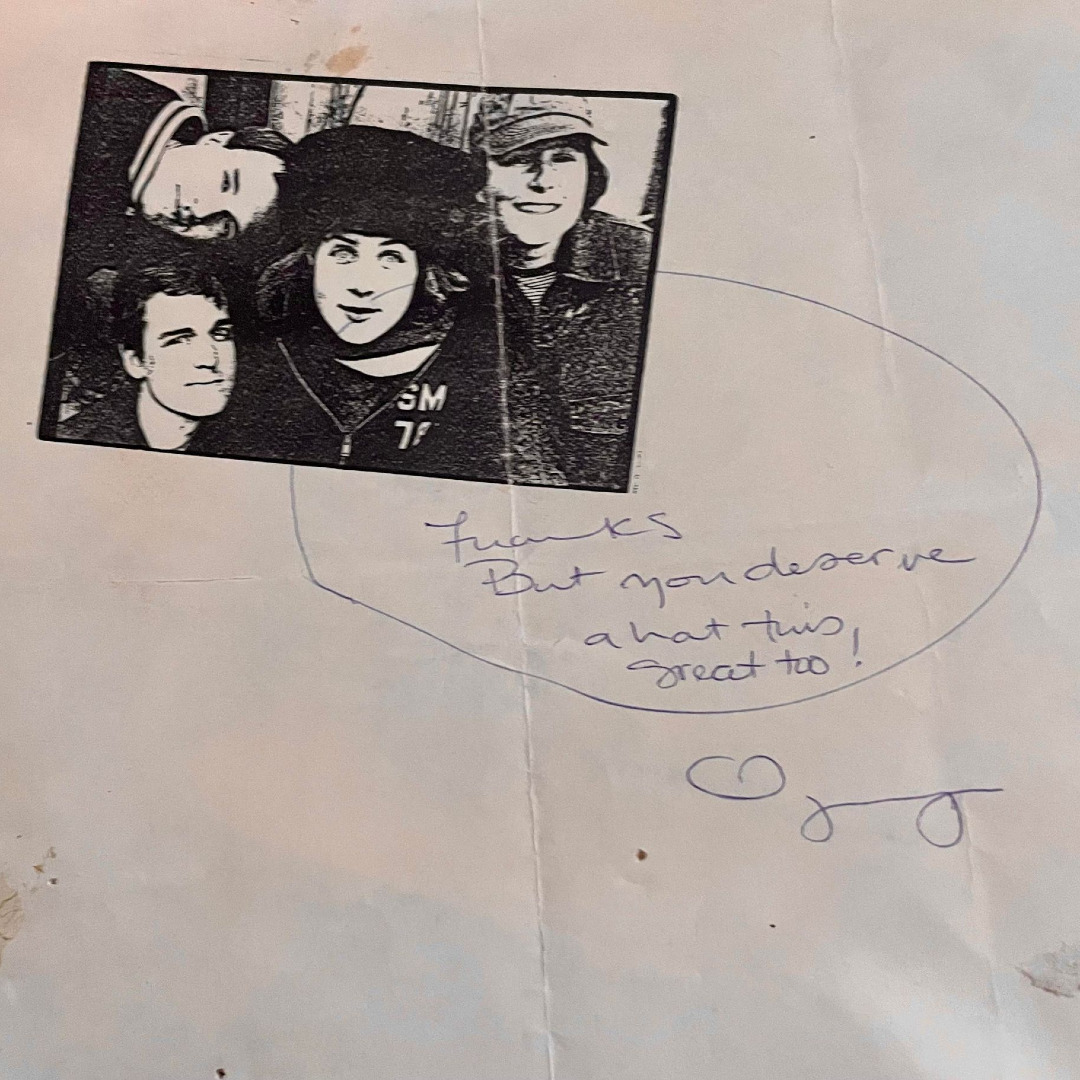

Jenny: I feel the same way. Kristin is such a special person. She’s just incredibly open and generous. She shows up with no guile or angle. She’s enthusiastic and game for anything. That’s 100% true. How hard is it to be best friends with someone who’s that great? More importantly she always does what she says she’s going to do. We both have a lot of that in us, which makes it possible to imagine and execute crazy ideas because we will try to do it together. We have so much history, a shorthand and a shared sense of humor. We fill in each other’s memories about what happened. Numero asked us to do this a couple of years ago or floated the idea, and I don’t know if we knew we wanted to do it yet. We were sort of confused. It all seemed kind of strange and maybe too good to be true. Now that we’re in the middle of the work, it’s been a joy to dig through suitcases with Kristin.

Kristin: In addition to the box set, Numero said, OK, we’re doing this big show last February (Numero 20) and got invited to play and we were kind of a last minute addition, it was maybe November, December, so we didn’t have a ton of time. A handful of Tsunami songs are quite simple to resurrect but as we got farther into the catalog it got harder and harder, only because we hadn’t practiced them in 25 years. I listened back to all the records in order and I was like, wow, these lyrics are good! It’s just something I hadn’t thought about in a long time. It was exciting to think about them again and re-remember all the lyrics and how dynamic and fun they are to play.

Jenny: We had this thing we started doing where a bunch of the Tsunami crew were part of my wedding band. Ida was our wedding band. They learned about 35 songs, and many friends did guest spots. At our 10th wedding anniversary, Brian suggested getting the wedding band back together again to hang out. We rented this massive rocketship of a house in Rhinebeck, NY. It was so much fun. We had a karaoke machine in the living room so we could sing and play games. It was so awesome that we have gotten together every year afterward and it reconnected us all together. So we had a bit of a glide path when Numero asked us because we were already back in each other’s orbits. And then it was so much fun, like when we were practicing. I remember John Pamer said, “I just had this strange feeling like I’m 19 years old.” Playing old music does bring back the emotions, though we’ve had to do a lot of work to hit the notes again.

CF: What about sexism and hecklers? Were there any bad soundman stories or like or uncomfortable encounters on tour, weird celebrity meetings? Did you meet Perry Farrell?

Jenny: We had a lot of all of that.

Kristin: I felt like it wasn’t so bad. It was fairly easy to have a clever retort or avoid it if necessarily. Jenny, there was one time we played in Oberlin and you told the soundman “no reverb” and he kept adding reverb just to taunt you.

Jenny: I don’t remember that kind of stuff. With the heckling, the audience wants you to win. So, it’s pretty easy to turn it around, and I can be the mean one if necessary. I’m the yang to Kristin’s yin. All that stuff washes away, though. When you are younger, it feels like everything is a nerve, a pressure cooker. You don’t yet have the wisdom you get when you’re older, where you realize that none of that stuff is all that important anymore.

CF: Was that one of the most inappropriate venues for you to play? Or can you think of a place that was more inappropriate?

Kristin: I was thinking about this, this was so early. We played in Gainesville, Florida, in a bar that was basically like a shot and beer bar in college town Gainesville. I was like, this doesn’t seem fun at all! It was super-early in Tsunami so we played. The crowd didn’t care—they were riding a mechanical bull next to us. It didn’t matter.

Jenny: Yeah, and there’s that time we played at Notre Dame. There were three people in the audience. There was a dartboard on a wall to the right of the stage, and people were playing darts in front of us during our set.

CF: Those (Ivy League) eating clubs used to really pay the bills, though, didn’t they? Like Princeton’s Terrace Club.

Jenny: Oh yeah, the Princeton Terrace shows were awesome. We’re so lucky that my old bandmate from Liquorice, Trey Many, is booking this tour that we’re doing with Ida in the spring. When we were discussing where we should play, I asked if he could throw some of those university shows in. He gently explained that students these days might want young people to play. They don’t want a 56-year-old set of indie-twins performing. As for the inappropriate venues, we were often protected because of how we were in the world. We killed people with kindness or weren’t famous enough to attract the “just coming to fuck shit up” kind of people. But I remember in the ’90s. It wasn’t too difficult to find those assholes if you strayed into the “normisphere”. I remember going for a beer at that odd enormous brewery Bardo Rodeo in Arlington. A group of frat guys did something rude to me, and I called them out. In response, they immediately circled my boyfriend at the time and were screaming, “Do you wanna go?!” He’s like, “I don’t need to go. You didn’t do anything to me, but I’d be worried … because she’s mad at you. I wouldn’t want to be in a fight with her.” So he was cool and wouldn’t take their bait. But then they physically tried to push us outside. They were picking an actual fight! In retrospect, we were often protected from so much shit just by being in counterculture. It’s not like it was perfect, but if I had gone to a fraternity party once, I bet I would have experienced far worse than I ever experienced in punk rock. CF