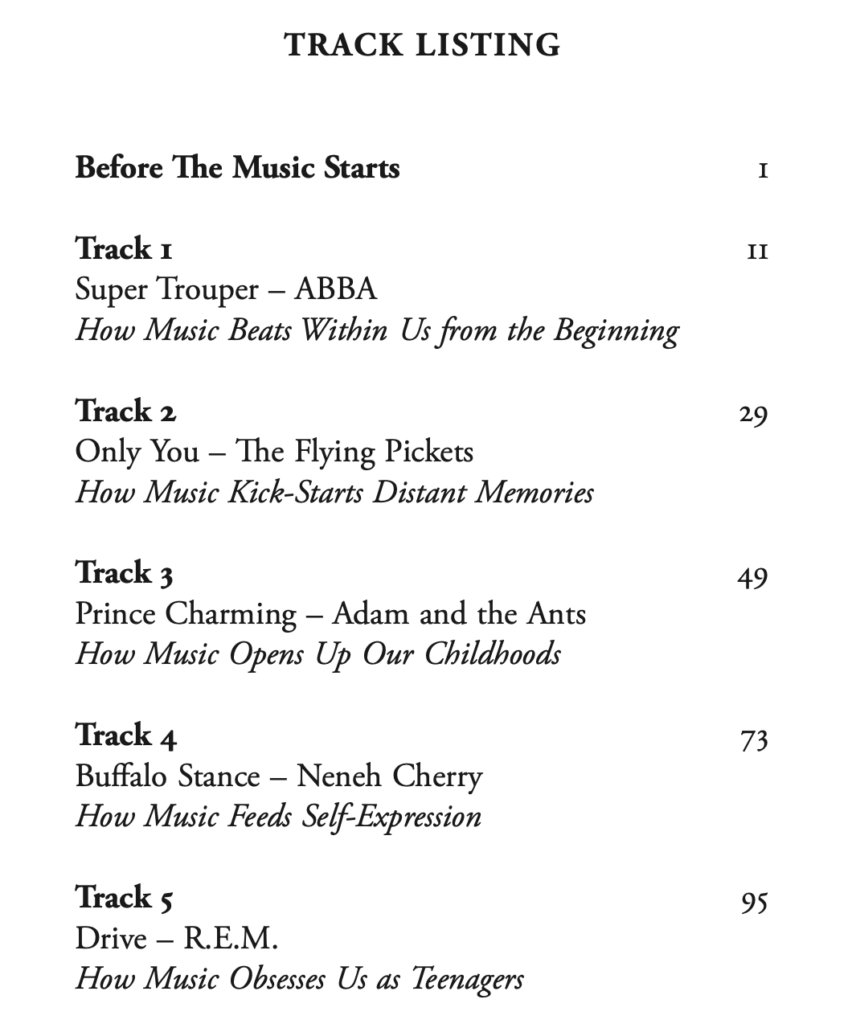

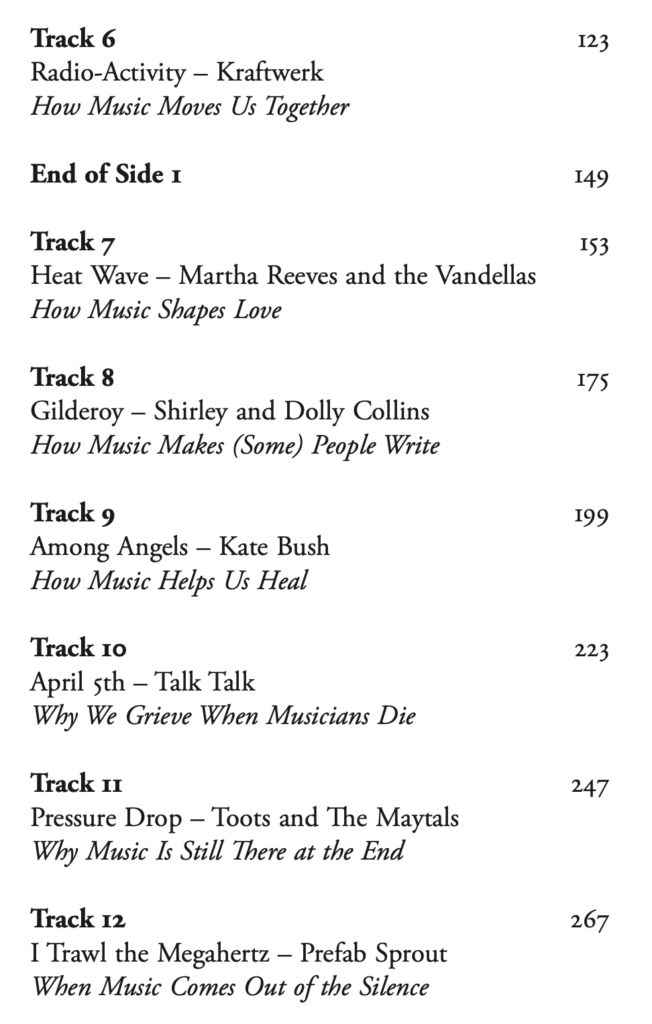

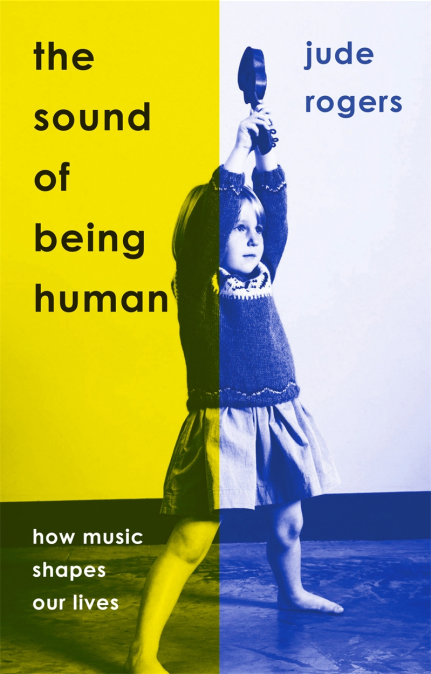

Many of you already know Jude Rogers for her wonderful music writing in the Guardian, the Quietus, the NME, and formerly Word and Smoke fanzine. Her 2022 memoir, The Sound of Being Human, is excerpted here on our very site: Read some of her chapter about being a super-fan of R.E.M. as a teenager. Her book is the rare memoir that manages to tell her story and teach us about the science of how music impacts our brains in a way that is both personal and universal. Here she talks about the book, which is just out in the U.S. and a perfect holiday gift for everyone you know, her own music history, her new podcast Songbook, which dissects music books, and tons more! Interview by Gail O’Hara / photographs courtesy of Jude Rogers

chickfactor: Tell us about your childhood and teen years. What music sources were you finding back then?

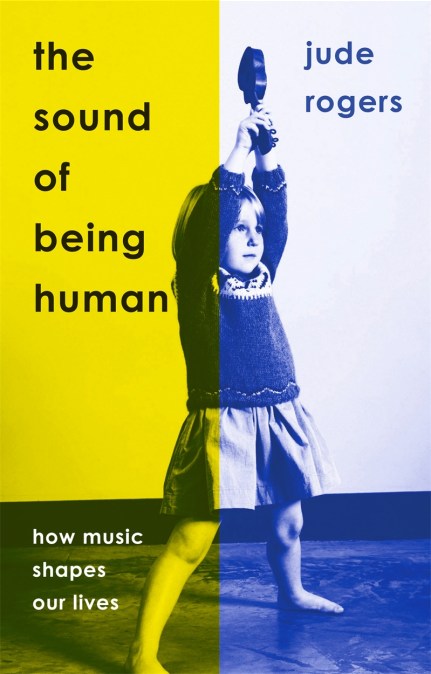

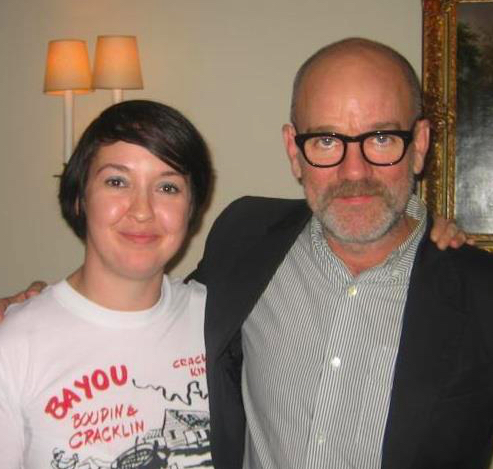

Jude Rogers: I was a big pop fan when I was really little, graduating to being a bit of an indie kid essentially at the exclusion of everything else for a while like a typical teenager, before I fell in love with all kinds of electronic music, back in love with pop, then in love with folk, et cetera et cetera. My first favorite band were R.E.M., who I talk about in very—what’s the word I’m looking for?—gushing teenage detail. From when I first bought Out of Time, that little trip to a huge Virgin Megastore and seeing this prized object on the shelves, and unfurling the concertina of liner notes, to my absolute love of Michael Stipe, I loved writing about that journey of fandom, when you’re watching videos and replaying them and listening to songs and the lyrics are just for you. How you’re sort of controlling that narrative in a way and the power that you have is really interesting, especially for teenage girls. You’re accessing other worlds and shaping your future along with that.

I found a lot of music through TV when I was a young kid, through Saturday morning British television and pop stars that would appear there for interviews, people like Adam Ant, George Michael, Neneh Cherry—who I found through Top of the Pops, the big British Top 40 chart show—and Kylie Minogue. I grew up in the ’80s, which was the time when the pop video became obviously gargantuan in its importance, its relevance, its budgets. Then in the ’90s, I fell for radio, which I write about with much love in my book too. Taping off the radio, especially taping cassettes off my friend Dan, whose Scottish sailor dad got a job parking ships in the United Arab Emirates, of all things, after he left the navy, and he’d bring us back dodgy pirate copies of PJ Harvey albums, Tori Amos albums, loads of stuff. I was quite into CDs in the mid-’90s too. Any way I could find music I’d find it. Oh, and buying 7-inches from Sullivans Record Shop in Gorseinon, the tiny town next to the village where I lived—it was my local tiny record shop, where I bought loads of singles and albums. I remember buying Come on, Feel the Lemonheads there and Elastica’s first album the week they came out and being very excited.

Tell us about the book.

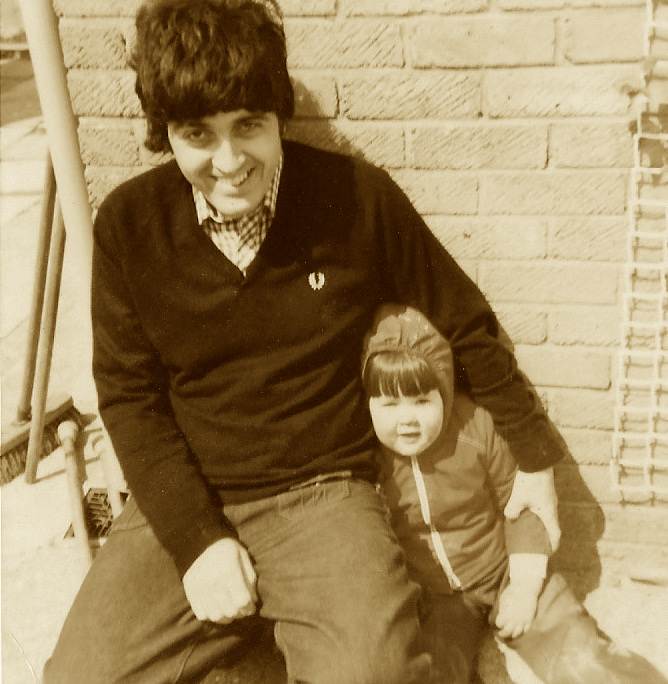

The book is out just in the US and published by Hachette. It came out in November in the U.S. It’s been out in the UK since April. Yeah, it’s got some really great press. Ann Powers loves it, hurray! And lots of other American people too, which is cool. It’s about how songs shape our lives in so many ways, taking me through the story of my life, from my first memory to the death of my father when I was five, through childhood, adolescence, crushes, falling in love, becoming a journalist, parenthood, grief and growing up—all soundtracked by songs. I speak to neuroscientists, psychologists, fandom experts and so many other people to find out why songs shape us so intrinsically, comforting us, enthralling us, propelling us back to the distant past, and into different future lives.

Tell us about the teenage brain on music (or your teenage brain on music). Which pop stars stayed with you and are you still fans of today?

I talk about this in detail in my book with the amazing neuroscientist Catherine Loveday. I love the part where she talks about another neuroscientist who went into an fMRI scanner to see what happened to her brain when she had an orgasm—she made herself have an orgasm—and the same bits of the brain get activated when we listen to our favorite parts of music. I think that says a lot! We really respond to music in that way when we’re teenagers because our brain is developing at this incredible rate—and we still remember that intensity when we’re older. I can listen to Automatic for the People and I’m in some sort of mad, beautiful reverie still. I love it.

What is the essence of the relationship between musician and fan?

It can be all kinds of things, but at its best it can be a love story, can’t it? You fall in love with a band or artist’s way of expressing themselves, their delivery, their lyrics, the way they craft music. It’s quite extraordinary. It’s not really with them as a person, it’s with this abstract but incredibly concrete thing that they have created. To share that with people is quite something. It’s funny having written a book and I’ve had lots of people at festivals come up to me and say, “God, I loved your book, it was great” and that’s wonderful, but it is weird thinking that people get really moved by something that you’ve made. What must that be like for a massive musician or somebody who’s engaged with a larger community of fans? And music works differently to words—it activates more parts of the brain and it encourages your sense of personal identity aside from your family, as well as your social sense when you’re interacting with others. Music is very strange and magical because our reaction to it is emotional and it’s profound and worth sharing. It’s the stuff of life for people. It’s intense. The essence of the relationship between music and fan, musician and fan, is intensity.

What is your favorite anecdote or quote from a scientist you interviewed in your book?

Definitely the orgasm one, although I still love the experiment about “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” in the chapter about babies in utero and how some babies remembered specific versions of the song after they were born. For my UK launch party for the book back in April, the amazing DJ and musician Richard Norris—who I interview in the book elsewhere about music and healing and how music can comfort us in times of trauma—did this amazing mix of me reading a part of the book with versions of “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” in the background. I also did a reading from the last chapter about “I Trawl the Megahertz” against an instrumental mix of the song that was structured the way that the rises and falls of the song could have met with my chapters. It was magical doing that. I really want to do that again. Richard and I are thinking we might record it actually, cause it just works so perfectly.

I had a relative with Alzheimer’s years ago who seemed to respond to music more than anything else. What did you learn about how music stimulates memory?

I love the chapter about music in later life, in which my main interviewees are two of my best friends, for whom music and memory is hugely important. One is the wonderful writer Kat Lister, who wrote an amazing book called The Elements about being her first year being a widow. She was married to the wonderful music writer Pat Long, who many chickfactor readers will know from the NME and other places. Wonderful guy. I talked to her about music and funerals. Pat knew he was dying, he had cancer, and he chose the songs for his funeral. In that chapter I interviewed her along with my friend Jess George, one of my very best friends, who works in dementia care as an occupational therapist—she talked to me about her working experience of music and memory with her patients, how music is absolutely one of the last things to go from your mind. And I also talked to an amazing palliative care doctor called Mark Taubert, who in 2016 wrote this amazing letter to David Bowie after David Bowie’s death thanking Bowie for his album, Black Star, which stimulated conversations in his palliative care practice with patients. A song kind of gets timestamped really into a lot of other sensory information in our heads. My chapter about “Only You” performed by the Flying Pickets talks about this as well. I wanted to know how and why it is that when I hear that song, I don’t just remember my father, I remember the last time I saw my father, where we were, the doorway, our whole world—and I do a lot of digging into research and doing interviews to find out why.

How did you start out as a music writer? Who are some other folks you learned from along the way?

Literally? I used to pick up the Top 40 charts from a shop called Woolworths in Llanelli, the small Welsh town nearest to where I grew up, where I used to work at the weekly newspaper on Saturday mornings. I was in my mid-teens and one of my tasks was to go to Woolworths, pick up the charts and type it up. So, if that counts as music writing, then there! Otherwise, it was through starting a fanzine when I was 24 with a friend of mine I had got to know through going to gigs—a guy called Matt Haynes, who I’m sure indie fans and chickfactor readers know. Matt was one of the cofounders of Sarah Records and later Shinkansen. I’d become a fan of a Shinkansen compilation, Lights on a Darkening Shore, not long after moving to London in my early 20s, met Matt at a gig at a merch table and started chatting about my new hometown. I was new to London and a bit obsessed with weird little secret stories about the city and he was born in London and knew lots of odd, geeky things. We thought, let’s make a fanzine about London (Smoke)—like a love-letter to it—and we did that in 2003, and it ran for years. I sent a copy to a music, film and books magazine called Word, where it was featured, then they asked me if I wanted to write for them, and six months later, in September 2003, I’d given up my horrible job, taken a pay cut of half my salary to go make tea, open envelopes, and hang around in the Word offices. I quickly got loads of reviewing work and started learning a bit more, but yeah, that’s how it started. I was with these amazing journalists, UK editors Mark Ellen and David Hepworth, who had been TV hosts in Britain of Live Aid and used to present a show called the Old Grey Whistle Test. They’re a really funny double act. There was an amazing guy called Andrew Harrison, still a really good friend, who is one of the best editors I’ve ever had. He was editor of the brilliant Select magazine in the UK in the mid-1990s, my period of reading it, and at Word he was my features editor. I couldn’t quite believe it. Paul Du Noyer, who I write a lot about in my book, was the reviews editor, an amazing quiet, clever, incredibly funny Liverpudlian who mentored me. Plus, lots of other great colleagues including the art director Bad Keith and ’70s Mike, the production editor. There were all these characters. It was amazing.

What are some funny stories from interviewing musicians or engaging with music you’re writing about or seeing live?

Lady Gaga once danced over my lap in her pants, bra and leather jacket while filling my glass with whisky—this was backstage in the London O2 Arena in 2010, and she was previewing her new album to me and a few other broadsheet journalists like Caitlin Moran. The next day I was working as a lecturer, and the kids couldn’t believe where I’d been! When I interviewed Kylie Minogue, I asked her about her Welsh roots—I’m from Wales—and we ended up talking about her grandma who still lived in the Welsh valleys, and Kylie tried to say this incredibly long place name in Wales from North Wales, which I won’t say into the tape, but she did it brilliantly. That was funny. Then there was the whole meeting your heroes, not sleeping before the interview scenario that I had with Michael Stipe, my teenage hero. That’s chapter five of my book! Did it go horribly wrong? It didn’t go horribly wrong, but the buildup to it was absolutely terrifying. I loved writing about that. ¶ I didn’t write in the book about my crowdsurfing fingernail-down-the-arm injury that lasted for 10 years after seeing Sonic Youth at Reading 1996 but maybe that’s one for the US paperback!

Did you ever receive a mixtape from someone and spend hours deciphering its meaning?Of course. I’m a woman who grew up in the ’90s!

Was there a time when you had a demystification moment, where you saw a musician you admired turn out to be a not-great person? Do tell.

This isn’t quite what you’re asking, but before I was a journalist, when I saw Michael Stipe live on a stage and he was a human being—which I also write about in the book—that was such a weird thing to me. It also didn’t help that this was R.E.M. in the Monster album phase, which did not fit in really with my love of the mysterious R.E.M. of Automatic for the People! Also my hero was being shared with lots of other people—but he’s mine!—and there were those people there just singing and not really listening … that was a weird demystification moment. Meeting people, I’ve been pleasantly surprised, to be honest, most of the time. I guess I haven’t met anybody who’s that unpleasant. Marianne Faithfull was as amazing as you’d hope she’d be, quite formidable, but also quite wonderful. Chrissie Hynde is somebody I thought was fantastic. I was a bit scared beforehand, but we got on really well and she did a painting of me! And at the end, she just took me into her little studio in her surprisingly modest home in a not particularly lovely part of London. And yeah, she did a painting of me, which is now on the side of my office behind some books because I don’t know what to do with it! My husband keeps saying I should have it like behind my desk like a big boss in a film—you know, like an oil painting of a tyrant! He’s joking, obviously. But it’ll probably end up, you know, in the loo, where it will have to be stared at people while they’re having some downtime!

I didn’t have a great time interviewing Alex Turner from the Arctic Monkeys, who wasn’t having a great day—so much so that I told him off. He clearly didn’t want to be interviewed—I was speaking to him for the NME—and the interview ended with me saying, “Alex, come on, you know, you didn’t have to do this interview.” I gave him a proper Welsh mum dressing down, told him off! But it’s probably not great being interviewed by 10,000 music journalists every day when you’re having a bad day, is it? I’m getting more sympathetic in my dotage.

You grew up when the internet was changing the way we interacted with music as fans. How do you see kids (your own?) now engaging in new ways that are completely different from your experience as a young fan?

I sent my first e-mail when I was 18 and didn’t get an e-mail address until I was 20, so I’m probably in the last age group of Western people to have a childhood and adolescence without the internet. I’m fascinated by how kids engage in new ways with music today. My son is 8 1/2. I write about him a lot in my book. Being his mom made me think about music in lots of new ways and very much inspired writing this book in many respects. But he’s now at the age where he has his own playlist—it’s called “110% best ever songs,” which I love. And I’m just profoundly jealous that he can hear the radio and say “put this on my playlist” and instantly any piece of music from the past 50, 60, 70 years he can put on it. If you told me that when I was 8, it would have just been the most space age cosmic idea. His favorite song is “Come On, Eileen” by Dexys Midnight Runners—not encouraged by me although I do love that song—which he heard on the radio, and there’s stuff like Dr. Feelgood’s “Roxette” next to Ed Sheeran’s “Shivers”, Olivia Rodrigo and loads of modern pop. I’ve been quite enjoying getting into chart pop with him now. We now listen to Radio 1, the UK’s chart pop station. It’s been really fun. But yeah, just talking to him about the way I’d spend loads of money to get music when I was young makes me feel so ancient. CDs were like 15 pounds when I was at university. That’s where my student loans went! But kids still engage with music—just in a much more instant way. I know anecdotally from friends with older kids that many of them aren’t as tied to albums as we used to be. But if the world of music was at your fingertips, I’m not surprised!

What are the tools you use now to engage with or find new music? Apps or analog?

I do a lot of rummaging around Bandcamp and SoundCloud to find stuff, which especially helps me write my folk music column for the Guardian. I also have friends who make playlists. My best friend Dan Cuthill, who I mentioned earlier, still has a playlist of new stuff that he updates all the time and I dip into that. My friend Kathryn who I mention in the Prefab Sprout chapter who does the same. And my friend Ian Wade, who I used to DJ with … you know, trusted friends are my guides. But reading The Guardian, Pitchfork, specialist sites like Tradfolk, blogs, listening to Radio 1 and Radio 6/BBC 6 Music over here is what I usually do. And Radio 3, which is classical and newer classical plus experimental as well.

What are some reactions or stories you got from people who read your book and wanted to share their tales with you?

I was very excited by getting responses from people saying, yes, I get this, I understand this! I’ll get the famous people out of the way first. Ian Rankin, the thriller writer, loved it and was very moved by my chapter when I talk about my miscarriage. That part seems to have affected a lot of people, especially when I talk about literally where it happened and how it started to happen when I was just about to interview Paul McCartney, the biggest interviewee of my life. And also there’s an actor over here and brilliant writer Ruth Jones. I don’t know if the show Gavin & Stacey has got any traction in the US but it was a massive sitcom here in the UK. She’s a brilliant screenwriter and has written lots of stuff for TV. She sent me a long message with all the things that the book reminded her of from her life, including a Kate Bush obsession in her early teens. That was wonderful.

I’ve also had lots of emails from people I’ve never known who’ve somehow found my address or sent me tweets. I had a man in his 70s, a retired head teacher who had read the book and didn’t know much of the music but was very moved by the experiences and identified with how music shaped his childhood and adolescence and adult years and later life, just from his different experience of being into classical music and different kinds of music. I found that very affecting. Also, recently I had an amazing message from somebody who had gone on holiday with some old friends. This was a bunch of people in their 60s and they all read and enjoyed my book and had made playlists for their holiday based on ideas from my book. And then they sent me the spreadsheet!

Tell us about some songs not in the book that you have strong feelings about.

What I haven’t put in and I’m still kicking myself I didn’t put it in the paperback is a song called “The Scarecrow” by Mike Waterson, which is an amazing song from 1972. Mike was one of the Waterson family, this amazing British folk-singing family from the northeast of England who had these tough, stark voices and learned lots of songs from their grandmother who brought them up when they were little because their parents died when they were all quite small. “The Scarecrow” is from an album called Bright Phoebus, and it was written by Lal, but adapted by Mike. I’ve written a huge piece about the Watersons recently for the Quietus website, and I talk in detail about “The Scarecrow” there. I’ll leave you to read that! It’s such an amazing song.

Is there a song you can’t listen to ever again?

I think I’ve got past that stage. There was a long period where I used to find “Fairytale of New York” very tough because it reminded me of a boy that I’d dumped at a bus station shortly before Christmas in 1998 who for a while thought I shouldn’t have dumped! And that song always took me back to him for a while. It doesn’t anymore. And obviously “Only You” by the Flying Pickets is a song that I have found difficult over the years because it takes me back to my last moments with my dad, which I talk about my book. My dad asked me, age 5, to find out—just before going to the hospital to have a hip operation—what was No. 1 and it had been “Only You.” Originally it was a song by Yazoo, who were called Yaz in the states (Alison Moyet and Vince Clarke), but it was covered by a Welsh band called the Flying Pickets. They had been No. 1 over Christmas 1983, then my dad went into hospital in early January. The No. 1 became “Pipes of Peace” by Paul McCartney, but I never had a chance to tell my dad because my dad died in hospital. And I used to find it very hard hearing “Only You,” especially as it was a Christmas No. 1, so a song that generally just pops up once a year at Christmas, and caught me unawares in quite a sudden, shocking way. I haven’t heard it yet this year.

What’s something that makes you jump up to dance?

Recently, “I Wanna Dance with Somebody” by Whitney Houston randomly came on the radio, and that is the ultimate, isn’t it? What a song! In my teens, I started to kind of sneer the things I’d liked when I was a bit younger – hating the high notes of Whitney Houston, and the melisma of Mariah Carey. Fantasy, that’s another one! What an idiot I was. I soon grew out of that. I love dancing to “Heat Wave” by Martha Reeves and the Vandellas, which I write about in the context of love songs in my book, that was the second song at my and my husband’s wedding party. Oh and “The Night” by Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons is such a fantastic song to dance to with friends, although that’s an interesting song for me now because it reminds me of the first COVID lockdown in 2020—it’s the song that really got me through the early days of that. It makes me feel quite sad hearing it now, but hopefully that will pass.

If you were a song, what song would you be?

Probably something ridiculous. You know, I would like to be “Heat Wave” by Martha Reeves and the Vandellas or “Cruel Summer” by Bananarama or “Venus” by Shocking Blue, but I’d probably be something far less cool.

What is the best TV or movie soundtrack ever made?

Twin Peaks, probably. I’m probably just saying that because Angela Badalamenti just died but that had a massive effect on me when I was 12. I watched that on a black and white television—a tiny television—in my room and didn’t see it in color until the DVD reissue. It was quite scary seeing scary Bob in black and white! But that music is so incredible. Other movie soundtracks…does West Side Story count? Probably not, but I’m having it! Those songs are so beautifully structured. I studied music at school until I was 18 and I’d love to look at the score and pick apart the movement of the melodies and harmonies.

What are some other music books you have loved in recent years?

There’s so many. There’s been such an explosion. From this year, I really love Jarvis Cocker’s Good Pop Bad Pop and Cosey Fanni Tutti’s book, Re-Sisters, but there’s been so many more. PP Arnold’s book I found really interesting about growing up and becoming a backing singer for the Ikettes in the ’60s with a background of a terrible marriage. There’s a Pauline Oliveros reissue I adored too. In recent years, I’ve loved Tracey Thorn’s books, which are wonderful. One of hers that’s less talked about is Naked at the Albert Hall, which is a great book about singing. I loved Viv Albertine’s book like every right-minded person, but I’ve also started this year doing a podcast called Songbook, where I explore great music books with my guests and there’s all sorts in that. For example, I revisited Fred & Judy Vermorel’s Starlust with Brett Anderson, a book of filthy fan letters, which was lots of fun, especially as I’ve been a fan of Suede since my teens. I discovered a great slim academic book called The Folk by a guy called Ross Coles thanks to the brilliant broadcaster Zakia Sewell, and got Vashti Bunyan to read Marianne Faithfull’s memoir, and went to Shirley Collins’ house to talk about her old boyfriend Alan Lomax’s The Land Where the Blues Began. I often review books too. I love so many!

What are your plans for the book over here? Events?

No events yet. But I would absolutely love to do stuff over the US at some point. If you want me out there, get me out there. I’ve got friends in LA and extended family in Colorado and New York. I’ll get a mattress on the floor, a sleeping bag. I’ll be out there.

What are five or ten records you cannot live without?

The 12 tracks that make up my chapters of the book are my way of trying to do this, I guess, but there are some songs toward the end of it which I include which I’d missed out. In recent years there are songs like “You Forever” by Self Esteem, I can’t imagine living without that. She is so brilliant. I can’t imagine living without “Freedom” by Wham!, who I managed to sneak into Chapter 3. The ones that make up my book, though, I think it would be them, because they’re the ones I chose to tell my story and they’ve got even deeper meaning for me now. When you pick records about your life, like the Desert Island Discs radio show here in the UK, you don’t think just about the songs. You think about all the places those songs take you to, the people they take you to, the worlds wrapped up in that. So, I’d have to go with them. I think the 12 of my book are a pretty good soundtrack to my life.